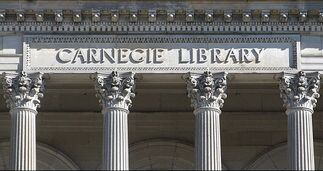

Our students are nearly out the door in June, when we in Core Virtues programs invite them to celebrate our heroes. We put before them rich and often little-known stories of those who lived exemplary lives, taking noble action against great odds for a good cause. It’s very unfortunate that June is a short month in many schools because since 2014, June has also been recognized as national “Immigrant Heritage Month.” And so many of our immigrants have lived exemplary lives and contributed heroically to the national experience. We think about John Muir (Scotland), Joseph Pulitzer (Hungary), Elizabeth Blackwell (England), Andrew Carnegie (Scotland), Samuel Gompers (England), Mary Harris “Mother” Jones (Ireland), Jacob Riis (Denmark), Irving Berlin (Russia), Albert Einstein (Germany), Audrey Hepburn (Belgium), Madeleine Albright (Czechoslovakia), and Henry Kissinger (Germany). And so many others. We know all these names (or many) but perhaps didn’t realize that they were all immigrants. Are their accomplishments in any way related to their choice to leave a hard reality behind and begin again? Young Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy put this topic on the national radar in 1958 with his volume, A Nation of Immigrants. JFK (and Oscar Handlin before him) reminded us that not only are we (almost) all immigrants or descendants of immigrants, but there is something about the act of emigrating – deciding to leave one country behind and by choice forging a new life in a new land, that fits its participants for at least success in America if not heroism. Why? Immigrants almost invariably have a sense of “agency.” They may have endured horrible circumstances, but they do not see themselves as powerless victims of horrible circumstances. They see themselves as creators of their future, doers. They summon all the resources at their disposal (ranging from courage to cash) to actively seek a better life for themselves and their children. They frequently encounter scorn and derision, discrimination based on language, race, and culture. But they work extraordinarily hard to achieve their dreams. They have higher levels of what Angela Duckworth has described as “grit,” and they are frequently described as “high hope individuals.” “Immigrants – we get the job done,” is the line from Hamilton that prompts a nightly wave of applause on Broadway. We intuit that is true. And the evidence? Consider this: immigrants are entrepreneurs at disproportionately high levels. In 2019 nearly 22% of all U.S. business owners were immigrants, though foreign-born citizens made up just 13.6 percent of the population and 17.1% of the U.S. labor force. In 2016 a full 40% of US Fortune 500 businesses were owned by immigrants or their children. Google Co-founder, Russian-born Sergey Brin, and South African-born Elon Musk (founder of SpaceX, Tesla, Twitter) are ongoing testimony to America's immigrants contributing mightily at the highest levels of the economy, as well as in positions of service and manual labor.  And historically, immigrants have been not just economic contributors, but effective agents for national and social progress. Scottish-born John Muir explored, wrote, and worked tirelessly to create and preserve our national parks. Hungarian-born Joseph Pulitzer strove to advance free speech through his newspapers and supply a home for freedom’s symbol, the Statue of Liberty. British-born Elizabeth Blackwell, our nation’s first female physician, founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, and started the first medical college for women. Muir’s fellow Scottish immigrant Andrew Carnegie created not just a steel empire but a network of 1600 plus free libraries. More than one aspiring American poet (such as Langston Hughes) credits his/her early immersion in literature to the Carnegie Libraries. The list of contributions goes on. There were the rabble rousers: Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, of Irish birth, who was not afraid to draw attention to the plight of American labor (sometimes in Carnegie’s own steel mills), and demand change. There was Danish-born Jacob Riis, who used his camera to document How the Other Half Lives, and to spur calls for decent living conditions in our city’s worst tenements. There was Irving Berlin, the little boy from Russia who lived in one of those tenements and was a different kind of rabble rouser: he had a song in his heart early on and lifted our spirits by composing such hits as “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” “God Bless America,” “Give Me Your Tired,” and “White Christmas.” And we could continue this sort of recounting right up to modern times.

America has a rich and expansive immigrant history, and we build on it with each generation. That doesn’t stop American citizens from going elsewhere sometimes. A former student of mine fell in love with France and spent YEARS working in and trying to become a French citizen. He eventually succeeded and his long legal quest to become part of the Gallic republic is for me a reminder that every nation has the right to control its immigration. I’m a bit passionate on the topic of US immigration because I’m married to an immigrant (from Chile) who is an engineer, entrepreneur, and fruitfully engaged citizen. So, even as we recall that every country has a right to secure its borders and decide paths to citizenship, let’s recall too that those knocking on our doors are more likely friends and assets than foes and enemies. And it’s good to know their stories. Mary Beth Klee

1 Comment

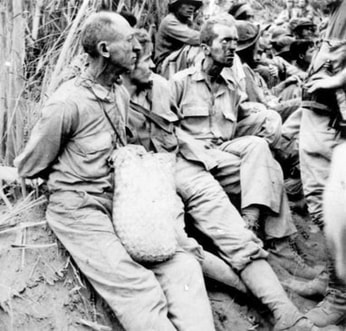

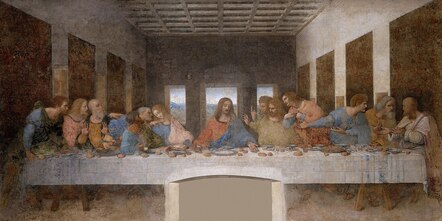

We ran a version of this article in May 2020. But its conclusions are even more timely as research on "hope" grows in the field of positive psychology. Hope, we are learning, is not an optimistic feeling, but an openness to seeing possibility in what lies ahead and -- even as we mourn loss -- an embrace of new opportunities.  So begins Emily Dickinson’s poem about one of the three great virtues, and it's a beautiful poem, but my reflections on Hope are grittier. Hope Johnson Miller was thirty-eight-years-old when she was captured by the Japanese and became a prisoner of war. An American school teacher married to a mining engineer, Hope and her husband had made their pre-war home in Manila, where they had a lovely home, servants, a driver, and shared the social life of American ex-pats overseas. As tensions mounted with Japan in late 1941, Hope’s husband answered General MacArthur’s call to enlist in the armed forces. Hope was alone in January 1942, when the Japanese invaded the Philippines, and imprisoned four thousand Allied civilians in Manila’s Santo Tomas Internment Camp (STIC). Three years of overcrowding, disease, cruelty, and starvation followed. Hope, who hailed from New Hampshire, had a gravelly voice and a granite-edged intellect. Known for her acid humor and the cigarette that was her constant companion, she was not the poster child for an Emily Dickinson illustration. No “thing with feathers” she. But over the next three years she taught those she befriended about the virtue for which she was named. Here are some lessons she taught. Hope endures: by late 1942 Hope learned that her husband George had been captured by the Japanese, endured the infamous Bataan Death March, and perished in the hell hole military camp of Cabanatuan. Stories about the cruelty of that march and that camp had filtered into Santo Tomas as early as August. When Hope learned her married life was over, she wept and inwardly raged, but she did not wallow in paralyzing grief. Instead…. Hope works: she labored, losing herself in the needs of the camp’s children. The camp’s industrious grown-ups had set up a makeshift school for the seven-hundred imprisoned kids. Hope now returned to overcrowded, makeshift classrooms and taught fifth graders. A devotee of American literature and poetry, she relished introducing her young charges to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (“The Song of Hiawatha”), Walt Whitman (“I Hear America Singing”), John Greenleaf Whittier ("The Barefoot Boy") and the newly popular Robert Frost (“The Road Not Taken”). She was a demanding teacher, who insisted on diagramming of sentences and memorization of verse, and STIC fifth graders both feared and admired Mrs. Miller. They admired her all the more when Allied bombers and Japanese Eagles tangled in the skies over their rooftop classrooms in 1944 spewing shrapnel and dropping bombs, and Hope insisted on being “last off the roof.”  Hope plans. Though she clung to the dream that American troops would soon liberate them, Hope did not put her trust in imminent release from danger. By late 1944, STIC prisoners were dying each day of starvation: she herself weighed less than 90 pounds. On September 22, 1944, the day after the first American planes overflew the camp and bombed Manila harbor (signaling to internees that help was on the way), Hope was on her knees outside her shanty, planting a little garden. When confronted by incredulous friends, who demanded to know what she was doing when liberation was only “days away,” she reminded them of the story of the Little Red Hen, and begrudgingly some decided to help her. Indeed, for the next four months that garden bore fruit (actually, spinach-like talinum, garlic, and mint) to tide them over. Hope draws on memory. Hope Miller’s memories were partly those of her Granite State girlhood at the foot of Mount Sunapee and of her husband, George. But hers was also the shared American memory: a sense of her nation’s story and her connection to it, a deep conviction that she was part of her country’s historic quest for freedom, liberty, and the wide open spaces that epitomized those qualities. For a Thanksgiving Day performance, after ten months of captivity, Hope had her fifth graders memorize and perform Stephen St. Vincent Benet’s, “The Ballad of William Sycamore.” In that poem, a Great Plains pioneer laments losing his two sons in battle -- one, at the Alamo and another at Little Big Horn, but “still could say, ‘So be it.’ But I could not live when they fenced the land, for it broke my heart to see it.’” On folding chairs, behind the iron bars of Santo Tomas, there was not a dry eye in the house. On Washington’s Birthday in 1944, Hope participated in a reading of Maxwell Anderson’s play, Valley Forge. Freedom, the play reminded these Americans in captivity, was often forged in time of trial. Endurance was part of the national drama. Hope shares. In mid-February, days after they were liberated, a young soldier sat next to Hope in the halls of Santo Tomas, staring at the emaciated men and women newly rescued and quietly taking in the cracked walls and squalid living conditions. While other GIs joked and chatted with internees, this “Still-Waters-Run-Deep” fellow put his hand on Hope’s forearm and said quietly, “Tell me. Did you ever despair?” In her written memoir, Hope writes, “My answer seemed very important to him.” And truth be told, if anyone had reason to despair it might have been Hope, who would return to the United States at age forty-one, widowed, childless, and penniless … to start all over. But instead, she couldn’t suppress a smile, took a drag from her cigarette and exhaled with satisfaction. “No. You see,” she turned toward the young man as if it were very important that he understand each gravelly word, “We knew you’d come back. We just knew it.” She held his eyes for a long moment and relished the childlike smile that suffused his face. Faith, hope, and love. In times of darkness, perhaps the greatest of these is hope. Psychologists tell us HOPE is not a feeling but a verb. It is the forward-looking, can-do reach for possibilities. True hope teaches us to endure, leads us to work, prompts us to lose ourselves in the needs of others, and draws strength from memory: our own treasured stories and those of others in our land, those who persevered in times of adversity. Hope ascends in an upward spiral when shared. Here's to Hope, my Sunapee friend and exemplar. Mary Beth Klee is the author of Leonore’s Suite, a novel about the experience of American civilians interned by the Japanese in Santo Tomas. Hope Miller's story is told therein and draws on Hope Miller Leone’s unpublished manuscript, Nor All Your Tears. In the gentle month of April three of the world’s major religions celebrate holidays that promote gentler selves. Ramadan came first this year. Beginning on March 22, this Muslim holy month is marked by fasting from dawn to dusk, prayer, almsgiving, and recitation of the Quran. Those who assist the poor in Ramadan are believed to reap special benefits. Passover, which begins on April 5 this year and continues through April 13, celebrates the deliverance of the Jewish people from slavery in Egypt; Jews fast from leaven, offer special prayers throughout, culminating in the traditional seder meal, which recounts the story of escape from bondage and God’s mercy. Easter, which this year falls on April 9, is preceded by forty days of Lent, also a time of fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. Christians are called to repent of their sins, and reminded that even from the cross, Jesus forgave his persecutors; they are called to love their enemies. Easter Sunday is, of course, the Christian celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus. Do these days and the practices that precede them matter? Well, look at the stats. We have a world population of approximately 7.8 billion, and in April a little more than half of us -- approximately 4.8 billion will be celebrating these feasts. That’s impressive: 1.9 billion Muslims, 14 million Jews, 2.8 billion Christians. Moreover, Buddhists (488 million) join Jews, Christians, and Muslims in recognizing humility as a path to Enlightenment. And Hindus (900 million) see forgiveness as a divine quality and urge the cultivation of humility as a path to spiritual growth. The world’s faiths, in other words, point jointly to some key self-effacing virtues – and more than half of the world’s population adheres to those faiths. Yet the self-effacing virtues are counter-cultural in contemporary society. “What is your superpower?” some college applications ask today’s students. Apparently, the next generation is expected to both possess and flaunt wondrous works. “Don’t get mad; get even” is another piece of common wisdom. Who needs forgiveness when you can have vengeance? Yet when psychologists Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman compiled their master work Character Strengths and Virtues, they logged forgiveness, mercy, humility, and modesty as essential qualities for temperance, the virtue of self-mastery. And science keeps proving them right.  In 2003 Fred Luskin, M.D. published a path breaking book Forgive for Good, and offered new insight into the medical benefits of forgiveness. His and subsequent psychological research has shown greatly reduced levels of depression, stress, anger, cardiovascular disease, and pain for those who practice forgiveness. Conversely, patient hope, confidence and immune response levels are higher for those skilled in forgiving. And a 2022 study by psychologists Lisa Ross and Jennifer Wright found that humility tracked with lower levels of neuroticism, greater love of life and higher openness to possibility. Other psychological research has established the importance of gratitude for emotional strength, wellbeing, and human flourishing. Forgiveness, humility, and gratitude are all traits that require a recognition that “the world does not revolve around me.” There is something higher. Which raises an interesting question: should our schools be teaching about these faith traditions and celebrations? Many schools, fearful of Church-state conflicts, dodge the topics, but the exemplary Core Knowledge Sequence has never shied away from them as key - at the very least-- to cultural literacy in our highly interconnected world.  In the Core Knowledge World History program students are introduced to the three major monotheistic religions in first grade (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), then introduced to Hinduism and Buddhism in second (partly in conjunction with ancient India); children do a deeper dive on the development of Christianity in third grade with the study of ancient Rome. They learn about the five pillars of Islam and medieval Muslim empires in Fourth Grade, as they do the spread of Christianity and an “age of faith.” They come face to face with the split between European Christians (Catholic and Protestant) in Fifth grade, and the fifth grade Renaissance unit – the extraordinary art of Botticelli, DaVinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo shows the artistic manifestation of these beliefs. Our modern secular age is of very recent vintage and exists side by side with a vast majority of believers (at least 6 billion). Parents are the primary educators of children, and they will decide in the home what they teach their kids about life’s ultimate meaning. But if we neglect the topic of world religion in schools, we fail to teach students what has motivated human beings over time and what still matters profoundly. By teaching about world religions in schools, we introduce kids not just to the past, but also to key wellsprings of wisdom, wellbeing, and virtue. Mary Beth Klee In March, Women’s History Month, we’re paying special attention to the challenges that young girls face growing into adult womanhood. Since 1987 our nation has celebrated “Women’s History Month.” That decision (a Congressional resolution) came on the heels of a 1970s feminist revolution aimed at opening for women any career path they chose and any future they deemed worthy. Let’s not stereotype women, was the message: women’s contributions need not be limited to home and family nurture; they have been and can be valuable contributors to economic and social wellbeing. The women’s movement of that era sought educational and professional opportunities equal to those offered men. Young women who came of age in the 1970s largely lived out those dreams and forged paths that would open doors for the next generation of women. In 1970, men outnumbered women at the university by 58 percent to 42%, but by 1980 the enrollment by sex was 50-50. Now women surpass men as a percentage. And career paths were unlimited: women became architects, astronomers, bankers, engineers, entrepreneurs, fighter pilots, etc. The Core Virtues Women’s History Month tab recommends numerous wonderful children’s biographies of the many trailblazers in those fields. And most of the women profiled, from Abigail Adams to Eleanor Roosevelt, were also proud to be wives, mothers, and homemakers. It would seem that with all this progress, there has never been a better time to be a woman.  A pioneering female student arrives at the University of Notre Dame in the 1970s. A pioneering female student arrives at the University of Notre Dame in the 1970s. But evidence from many sources suggests the opposite. Last month the Center for Disease Control (CDC) released data showing that teen girls “were engulfed in [a wave of] violence and trauma.” And we see that reflected in news stories. Online bullying incidents among girls have become toxic and tragic. Last month fourteen-year-old Adriana Kuch was savagely attacked by other teen girls in a New Jersey high school hallway. Bystander girls filmed the beating, then posted it on Tik Tok, with ongoing taunts about how she “deserved it.” Humiliated, ninety-eight-pound, five-foot-two Adriana, who loved animals and worked with special needs kids, committed suicide two days later. This is an extreme case with devastating consequences – but it is not isolated. Teen girls “beating up” on other teen girls via social media is now a national epidemic. For decades girls have been infamous for cliques that exclude those who are “not cool,” (satirized in the 2004 movie Mean Girls) but since 2007 “mean girls” have been armed with a new weapon: the smartphone. Amid screen-addicted friends, they spread shame, mockery, and self-doubt. No wonder the CDC finds that 57% of teen girls report themselves “persistently sad or hopeless,” and that 30% have considered suicide. Here's another alarming stat for the future of womanhood. One in five thirteen- to seventeen-year-olds are identifying as “transgender,” and the vast majority are pre-teen and teen girls who showed no sign of gender dysphoria (discomfort in the sex of their birth) in early childhood. What was once a rare psychiatric condition (until 2013 known as “gender identity disorder”) that manifested itself almost exclusively among pre-school boys who identified as girls--has become a social trend.  Girls as young as fifth grade are opting out of growing into adult womanhood. They cut their hair, change their name and pronouns, adopt male clothing, bind their breasts, and contemplate puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones, perhaps the eventual top surgery and phalloplasty. More than any other writer Wall Street Journal investigative reporter Abigail Shrier documented and analyzed this phenomenon of “rapid onset gender dysphoria” in her jaw-dropping 2020 book, Irreversible Damage: How the Transgender Craze is Seducing Our Daughters. She too found social media peer groups pushing this evolution and documents many of its long-term effects. These new developments bode ill for the future of womanhood. Girl-on-girl physical, emotional, and verbal abuse of the scale we are now seeing is new and frightening. It mirrors the behavior of fictional pre-teen boys in William Golding’s 1954 novel Lord of the Flies, in which cruelty, tribalism, and savagery come to characterize British boys stranded on a desert island. Typically, we did not associate this behavior with girls. And now young girls imagine themselves born into the wrong body and seek a new identity as males. Why are these behaviors developing among our girls? There are three answers: one psychological, one technological and the other cultural. Psychology first. Teens are a peer-driven group. This is the age at which young people seek to establish independence from parents, and strengthen their own identity and self-worth, often in tightly knit and trusted peer groups. Psychologists see this increased peer-group reliance as a not-necessarily-unhealthy step in emotional maturity. It is a way of both asserting young adult independence and acquiring emotional support by acceptance into a chosen group. Teen girls are particularly insatiable in their desire for peer group connection. When those peer groups are healthy (kids who are excited about learning, the arts, outdoor activities, sports, faith, or supportive of helping others) the experience is positive and a step in emotional maturity. When peer groups are power- and exclusion-driven (kids who see coolness in wealth, appearance, clothing, manner of speech, substance-use etc.) the experience can quickly become toxic. Such peer groups thrive on ostracism and the rising incidence of bullying in American middle and high schools attests to that. Throw into this mix our new twenty-first century companion: the smartphone, born as the “iPhone” in 2007. America’s parents have been reeling ever since. According to the Pew Research Center 88% of American teens own a smartphone (the average age of the adolescent user is 12-13), and as of 2019, 95% had access to one at home. 78% of teens check their phones at least every hour. 72% feel the urge to respond to their texts of phone notifications. 59% of parents think their teens have a smartphone addiction. On the surface, this tool of technology is morally neutral; it has the potential to connect, inform, and entertain us all. But the advent of social media has enabled online peer groups. We are seeing teen cyber-bullying, and in-group out-group exclusions on an unprecedented scale. Tik-tok, Snapchat, and many other apps have come vehicles for sharing mortifying photos, publishing cruel comments, and encouraging self-doubt and self-hatred particularly among young girls. Many teen girls live in fear of what will be said about them online--a forum they do not control. Other girls use social media to seek out a peer group that gives them both a unique identity and a support group. Count most of the newly trans teens among the latter. Vulnerable or just plain curious young girls find plenty of support online for ditching society’s and their parents’ expectations of them at the most basic level – their sex. Puberty for girls has always been challenging, involving physical pain and discomfort, emotional rollercoasters of mood swings, and a large dose of insecurity. And since the 1970s, we’ve been broadcasting loud and clear that on the other side of the puberty divide, men have the upper hand. Women have to be twice as good to compete. And women have the added “burden” of childbearing and home making. So, what could be more appealing than opting out of all that? Abigail Shrier’s book documents the near-universal phenomenon of these young girls’ deep involvement on social media forums that offer new and exciting peer groups. Trans peer groups advertise themselves as a new family, and even encourage teen distancing from their biological families, as they establish their new gender non-conforming identity. Again, often with tragic results. A recent case in Virginia led one fifteen-year-old girl to leave her family home and meet up with her “online family,” only to discover that she fled to the arms of human traffickers. Why are girls doing this? Because in the realm of culture we have an unfinished feminist revolution. The Core Virtues program highlights compassion, faithfulness, and mercy as March virtues. These are virtues for both sexes, but they have historically been most closely associated with women. The nineteenth century German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously held up the “eternal feminine” (ewig-weibliche) as the highest human ideal. “The eternal feminine draws us on high” were the words with which he closed his masterpiece Faust. That feminine ideal embodied such traits as beauty, truth, love, compassion, mercy and grace. It was embraced by American feminists Margaret Fuller and Edna Cheney. It’s no accident that our March Core Virtues “heroes” have been mostly “heroines” – Clara Barton, Anne Sullivan, Mother Teresa. Compassion, mercy, and grace are the qualities that have characterized not just significant social reformers, but also the familial pillars of our society -- good mothers. The 1970s feminist revolution (of which I was a part) broadcast the message: motherhood and homemaking is not the whole story. But often the subtext was: motherhood and homemaking are for those who can’t cut it in the “real” world of commerce, enterprise, or academia. Motherhood is a biological accident of nature, not a worthy aspiration. And please don’t tell me to be meek and mild. The message we have not sent our daughters in the last fifty years is:

I am taking a suggestion from Abigail Shrier’s closing chapter and asking that our March message to young women be: it’s great to be a girl. I’m proud to be she.

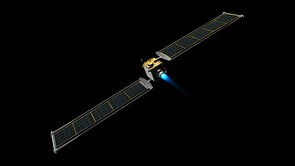

-Mary Beth Klee To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. Among the February virtues highlighted in the Core Virtues sequence is an old-fashioned one: love of country. In an age when we often speak of “global citizenship” and are alert to potential abuses of ethnocentrism, many of our schools and our general culture have tended to downplay “love of country” and quietly eschew nationalism. But we have done so to our detriment. In his 2017 article, “A Sense of Belonging” E.D. Hirsch Jr. drew attention to young people’s declining sense of attachment to their country and asserted that distancing has contributed to racial and ethnic polarization and “hyper individualism.” (“Out of one, many.”) Hirsch attributed the decline in large part to the failure of schools in the past six decades to teach substantive content (U.S. history, civics, biographies, poetry, songs) and to emphasize instead the primacy of the individual and his/her individual interests. Teach the child, not the subject has been the mantra. Lost in the process has been an understanding of our shared past, a sense of community, belonging, and solidarity with our fellow citizens. Much diminished is the devotion to country that spurs students to contribute to the advancement of something larger than themselves of which they are a part. Hirsch called for cultivation of “the right kind of nationalism” in American schools, one that educates about our past, our heroes and milestones, one that enshrines our highest ideals. “The right kind of nationalism is a very good thing,” he asserted. The right kind of modern nationalism is communal, intent on including everyone. The wrong, exclusivist kind, exemplified by the racism of the Nazis, gave all nationalism a bad name and helped turn the post-Vietnam left away from nationalism of any sort. The sentiment was that most countries are pretty bad, especially big ones that prey on little ones. When designing the K-8 Core Knowledge Sequence in 1991 and in updating it since, he and those who drafted the program abandoned the insular social studies framework of “me, my family, my neighborhood, my community” that had characterized elementary education since the 1970s (and in many schools still does). They substituted strong U.S. and World History programs. Children were encouraged to see themselves as part of the long arc of human history (beginning with the Ice Age, moving through ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, Greece, Rome, the Middle Ages worldwide, and modern times). And through their studies in U.S. history from first to eighth grade, students have been encouraged to see themselves as part of the American journey, which has been a worthy and unique one. Let’s go ahead and say it: an exceptional one.  The American Revolution with its trailblazing insistence that “all men are created equal” was not an immediately realized ideal. But the establishment of a republic on that principle, the principle of freedom and equality, was a radical departure from the norms of the times, when monarchy, oligarchy, and tyranny prevailed around the globe. At the time of the American Revolution, when those words were proclaimed, the vast majority of the world’s people lived in some sort of “unfreedom” as serfs, slaves, or indentured servants. (The American population itself was 20% enslaved.) 1776 was a root-level departure. And the entire American story has been one of living out the ever-expanding meaning of those words to include women, Native Americans, people of color, people of all races and faiths. When U.S. history is told fully and honestly, we see injustice in our past – as we do in world history. But from a historical standpoint, no nation has provided more opportunity to more people of more varied backgrounds than the United States. We do our children a disservice when we fail to tell these stories. Stories of key people and key moments in time, along with stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Surely, we should tell the stories of George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Abe Lincoln, but also Benjamin Banneker, Abigail Adams, Sacajawea, Clara Barton, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sojourner Truth, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass. Surely, let's focus on Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, John Muir, Dwight Eisenhower, but also George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells, Eleanor Roosevelt, Frances Perkins, Rachel Carson, and Cesar Chavez. These are the stories that instill hope and cultivate a shared love of our country and its ideals. Many, many of those are featured in our February “Virtue of the Month” tab, in our President’s Day tab, and on our Black History link, our Women’s History link, our Immigrant Heritage link. Many are immortalized in the Childhood of Famous Americans series, and many re-envisioned in the Tales of Young Americans series we spotlight in our February overview. In his last State of the Union address in 2016 Barack Obama called on Americans to listen to “voices that help us see ourselves not, first and foremost as black or white or Asian or Latino, not as gay or straight, immigrant or native born, not as Democrat or Republican, but as Americans first, bound by a common creed. Voices Dr. King believed would have the final word – voices of unarmed truth and unconditional love.” This month in our Core Virtues poetry section we spotlight Walt Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing.” Barack Obama updated that poem as he concluded his State of the Union address. "And they’re out there, those voices….they’re busy doing the work this country needs doing….  I see it in the worker on the assembly line who clocked extra shifts to keep his company open, and the boss who pays him higher wages instead of laying him off. I see it in the Dreamer who stays up late to finish her science project, and the teacher who comes in early because he knows she might someday cure a disease. I see it the American who served his time, and made mistakes as a child but is now dreaming of starting over – and I see it in the business owner who gives him that second chance. I see it in the protester determined to prove that justice matters – and the young cop walking the beat, treating everybody with respect, doing the brave quiet work of keeping us safe … That’s the America I know. That’s the country we love. Clear-eyed. Big-hearted….Optimistic that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word. That’s what makes me so hopeful about our future. Thank you, God bless you. God bless the United States of America.” Mary Beth Klee Dr. Klee holds a Ph.D. in the History of American Civilization from Brandeis University. To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. “Courage is moving beyond fear; it is having the strength to venture and persevere.” Sometimes intellectual and moral courage makes you an object of scorn and derision. Galileo experienced that. So did Martin Luther King Jr. But scholars and thinkers who pursue the truth know they will sometimes face headwinds. The Core Virtues nominee for intellectual and moral courage this month is Stephen B. Levine, M.D. of Case Western Reserve University. Dr. Levine, an American psychiatrist, is renowned for his five decades of work in human sexuality and gender dysphoria (discomfort in the sex of one’s birth). His expertise is of great relevance currently. In the past fifteen years, we have seen a huge uptick in pre-pubescent and teen girls who are experiencing what has been termed “rapid onset gender dysphoria.” Two decades ago, gender dysphoria was extremely rare – afflicting approximately one in ten thousand children. Those afflicted were generally little boys who identified as girls, eighty percent of whom outgrew the disorder by age eighteen. But since 2010, the incidence of gender dysphoria claims has sky-rocketed, and the fastest growing segment is pre-teen and teen girls. One in five 13–17-year-olds are identifying themselves as transgender, and the vast majority are girls who showed no sign of gender confusion in their early childhood. One Core Virtues school reported that four of their fifth-grade girls had recently declared themselves “trans” in class. These are eleven-year-olds who believe their identity and future does not lie in adult womanhood. They are changing their hairstyles, names, and pronouns, and thinking about binding their budding breasts. Do they know the next step in this journey is puberty blockers, then eventually cross-sex hormone treatments, which will lead to sterility? Many schools are struggling with how to respond to what appears to be a phenomenon driven by social media and peer groups. Dr. Levine’s work in the field of transgender care is extensive and exemplary. His presentation to the Pennsylvania State Legislature, which was considering funding for youth transgender care, is a clear-eyed and courageous presentation of what we know and what we don’t know about transgenderism and best treatment. He is taking a lot of heat for it. At a time when many physicians are accepting patient self-diagnosis and providing (lucrative) “gender-affirming” treatment even for minors, Dr. Levine takes a hard look at the evidence. He urges respect and compassion, but cautions against social affirmation as the best response for those under 18, and believes this may trap vulnerable young people in a life of diminished prospects. Bravo to him for the courage to speak truthfully about a profoundly troubling national phenomenon. Mary Beth Klee NB: Dr. Levine's presentation constitutes the first 52 minutes of this 1:27 minute hearing and constitutes the key material. To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page.  This month, when we spotlight the virtue of generosity, let’s also train eyes on generosity’s natural ally: hospitality. As families prepare to welcome relatives, friends, and strangers into their homes, we can help kids understand that the December holidays are not just a time to party, but a time to open our hearts and homes to the needs of others, to be a host and take joy in putting our guests first. AND let’s talk with kids about being good guests too. Hospitality, the friendly reception of guests or strangers into one’s home, has ancient roots. Early Bedouin peoples, who were always on the move, enshrined the virtue of hospitality in the Middle East. Offering shelter, water, finest food and drink, even music and stories to the traveling guest, was a feature of both ancient Sumerian and ancient Egyptian lore. Biblical sources repeat the theme. Ancient Greeks considered hospitality (philoxenia – “love of the stranger”) not just an option but a duty. In medieval times, Benedictine monks enshrined “hospitality” as one of their vows; they hastened to provide food and shelter to pilgrims on the move. So, as we deck out our homes, bake our cookies, put on the holiday music, and prepare to welcome guests, it’s a good time to remind ourselves and our children what it means to be a good host … and a good guest. When we extend hospitality, we are first and foremost thinking about the guest. We strive to create a welcoming space for the other. Our objective is to make guests feel appreciated and special. What should we teach kids about how to do that? It starts with getting ready: we prepare by providing a clean and possibly festive space, an area in which our company will feel welcomed. Maybe that means tidying up a play space or setting the table in a special way. When guests arrive, in the northern hemisphere at this time of year, it involves offering to take their coats and perhaps a bench to sit on to remove their boots. Then it’s about welcoming them into our home, letting the guests go first, and making them comfortable in the space in which we plan to entertain. By custom we offer guests a special drink or snack to welcome them. Then it's about sharing—learning about their lives, telling our stories, pursuing a common activity, whether a meal, conversation, card game, carols or karaoke. If you’re dining together, guests often have a special seat at the table. We can teach kids to clear the places of the guests at the end of the meal. When the guests leave, help them gather their belongings and always thank them for coming. Are there rules for gracious guests? Yes, indeed. The host does not expect payback but can expect good manners. The good guest gratefully accepts the hospitality offered and doesn’t ask for something different unless a physical allergy is involved (and then with apologies). The good guest always finds a way to express appreciation to the host for the meal or party or entertainment they’ve provided. And the good guest participates in events with gusto, responding eagerly to overtures of conversation and activity, contributing from their interests and experience. “Sharing” is not just about the host inquiring into the life and activities and needs of the newly arrived, but also about the guest seeking to better understand his/her hosts and contribute to a convivial environment with their own stories. Good guests leave the home of the host in good order (unless the host doesn’t really want them to help with dishes, which is common), and with many expressions of gratitude. In December, teachers can role play these situations with their class, having half the class be “guests” for lunch one day, and the other half act as “hosts.” Then switch it the next day. Who’s taking the coats? Who’ll show the guest to their seats? Who’ll serve the drinks and meal? How should the guests express appreciation? The class can also brainstorm how they can help their parents with the entertaining they are about to do: tidying the house, putting up the decorations, setting the table, putting guest towels in the guest bathroom, and much more. In Genesis, Abraham rushes out to meet three strangers who approach his tent and offers them hospitality. The ancient Jewish patriarch turns out to be "entertaining angels unaware" and is blessed by them. In our lives, when we discover the joy of opening our hearts and home to others and when we express gratitude toward those who honor us with their hospitality, the holidays come to life in a new way. Mary Beth Klee To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. We feature Charles Dickens this month as our hero, as he (and his writing) model generosity of spirit and charity. To accompany him, we reprint here an earlier December blog because these thoughts are timely, if not timeless.  When the Ghost of Jacob Marley appeared to Scrooge on that eerie Christmas Eve, the frightened miser noted that he could see right through him, from his waistcoat to his back – he “had no bowels.” What? The contemporary reader comes to a full stop at that line, but in the nineteenth century the meaning was clear: bowels were the organ associated with compassion and empathy. Much as we would use “heart” today. And in his three spectral journeys, Scrooge travels through the bowels of time to sharpen his vision of Christmas Past, Present and Future, and to grow in love for those in need. Charles Dickens’ nineteenth century classic A Christmas Carol remains an admonition to stay alert to the plight of fellow travelers on the road of life. It is ever useful because then as now, we tend to wear social blinders or get stuck in our lanes. Depending on our neighborhood or profession, those in need may be nearly invisible to us. We may see right through them – or past them. Just as those original Christmas travelers, Mary and Joseph, were invisible to the innkeepers who had a full house. In this season when we try to sharpen our vision and fortify our bowels, let’s consider assisting some of the literal travelers on the road of life: Ukrainian and Afghani refugees. Since Russia's invasion of the Ukraine and since our own country’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, thousands have fled and sought refuge here and abroad. More than 368,000 Ukrainians are fleeing to the west, entering Romania, Poland, and Moldova. Last year, more than eleven thousand Afghanis fled their Taliban-dominated home, and came to the US. In both cases, refugees been helped by the work of Dorcas International, a nonsectarian outreach group, which has dedicated itself to refugee resettlement, and making a home for the stranger. Groups like Dorcas International try to position these legally admitted newcomers for success in their new homeland. With both a professional staff and LOTS of volunteers, they arrange for apartments, for English language classes, for vocational training in carpentry and the trades, enrollment of children in schools, and family assistance with grocery shopping, as the newcomers get their feet on the ground. The needs are immense, but the folks from Dorcas and many other non-profit and church groups are there to welcome the “poor, tired, and hungry yearning to breathe free.”  But what about the poor, tired, and hungry who are here on our own shores already? The everyday Americans, who often, because of bad fortune or drug addiction or alcohol or mental illness or domestic abuse have lost their way and are on the streets? We cannot walk through our cities without being aware of the homeless: folks with their carts and their pets, with a pleading sign, and a hand extended. Nearly half a million of our fellow countrymen are homeless. On the Core Virtues site, we’ve featured the slender middle school novel Stay (by Bobby Pyron), which shines a light on those who live in Emergency Shelters and/or public parks. And we feature some moving picture books as well. When addressing the problem of homelessness, there are state and federal initiatives to be sure, but the national tradition of voluntarism and what used to be called “benevolent institutions” is still active and a way to extend a hand. This is the time of year to support the work of non-profit, non-partisan groups like the National Alliance to End Homelessness and the Salvation Army. Our personal contributions and turning the attention of our students to those these groups serve is a way to keep the spirit of the holidays. The holidays are a time “when Want is keenly felt and Abundance rejoices,” two bell ringers tell Scrooge. His “bah-humbug” echoes in our ears. But the miser became a changed man following that Christmas Eve journey, and it was always said “that he knew how to keep Christmas well.” May we too know how to keep the spirit of the holidays well even beyond the holidays. To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. As night hours lengthen in the northern hemisphere and the stars seem brighter this month, we’re entitled to stare up in awe. We see the brilliance of the heavens and the glory of shooting stars. Should we also stare up in fear? After all, 65 million years ago a massive meteor (six to nine miles wide) sped through the atmosphere, crashed into earth, and took out all the dinosaurs. Ten years ago, a sixty-pound asteroid plummeted to earth from space, crashed into Russia, and injured 1500 people in its path. What if a planet-killer ever headed our way? Could we somehow deflect it or are we defenseless? Fortunately for us earthlings, smart people at NASA and Johns Hopkins Applied Physics lab have been thinking about this. The Planetary Defense Coordination Office at NASA (surprise – there is one!) has been hard at work. On November 24, 2021, just a year ago, they launched a bold probe, sending a $325 million space craft the size of a refrigerator on a path to collide with an asteroid the size of a pyramid. The idea was not to explode the asteroid, but to nudge it off course. “Like throwing a tennis ball at a 747,” said NASA’s lead engineer Elena Adams. Use the momentum of the crash to give it a shove, and make it change orbit. Would it work? The asteroid selected, Didymos, was no threat to earth but it was conveniently located for a test, and it had a moonlet, named Dimorphos, that would serve as the target body to change the asteroid’s orbit. This “Double-Asteroid Redirection Test” or DART was a historic first: human beings were attempting to modify the orbit of a heavenly body. On September 26, just eight weeks ago, DART hit its target. A dramatic bullseye. It worked!  An illustration of DART's ion thrusters. An illustration of DART's ion thrusters. How could it not? Sending a 1260-pound spacecraft across seven million miles at a speed of 14,000 miles per hour and making sure, at the end of its ten-month journey, that it hit an asteroid moon so (relatively) small that scientists did not know its shape until just minutes before impact, when the cameras aboard would record its arrival. How could anything go wrong? Scientists at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics lab and NASA thrilled to watch DART hit its target and meet its demise, but the best news came in October (just weeks ago) as they confirmed DART had in fact changed the body’s trajectory. Earth’s telescopes had confirmed it. NASA’s goal was to slow the Dimorphos orbit by 10 minutes, but they exceeded their expectations and managed to slow it by 32 minutes, definitively altering the course of a celestial body. “This is a watershed moment for planetary defense and a watershed moment for humanity,” proclaimed Bill Nelson, NASA Administrator. It is technology that could protect all of us in the future. This Thanksgiving, I’m thankful that some people are looking up and thinking big. And that Earth is now a safer place. Bravo to those good stewards of our planet. Mary Beth Klee You can watch a presentation about the DART mission here. To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page.  In I Survived Hurricane Katrina, ten-year-old Barry dreams of being a superhero. His alter-ego “Akivo” accesses his superpowers through his pinkie and a star that sends special energy to guide him. When the young boy is swept away from his parents in crushing flood waters, he clings to an oak tree, a dislodged house, a grateful dog, and ultimately, to his hope of being reunited with his family. But he does more than cling: he shimmies up the oak, makes a leap for the house, unchains a whimpering dog tied inside, seeks out a dry patch of roof, and with the dog (named Cruz) waits for rescue. Barry’s is a fictional odyssey set during 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, which took the lives of more than a thousand New Orleanians. Lauren Tarshi tells the story well, and in persevering, the child comes to recognize both his own strength and what it means to have companions for the journey. He doesn’t go it alone. He literally embraces his cross (Cruz) and finds his way to safety and family.  Hurricane Ian, 2022. (NASA) Hurricane Ian, 2022. (NASA) In the last month, as Hurricane Ian bore down on the southwest Florida coast, many more have had the chance to persevere in the face of life’s literal storms. Preparing for disaster. Attempting escape. Enduring the wrath of wind and water. Living in fear and hope. Sinking, swimming, then, with luck, picking up the shattered pieces to move on. Some of us inadvertently persevered. The storm changed course at the last minute and when Naples became a mandatory evacuation zone on Tuesday evening, my husband and I decided to drive to Miami, ninety miles east where we had friends. It was getting dark. The storm wouldn’t make landfall till the next morning, but when we turned on to I-75, Ian was already upon us. The drive along “Alligator Alley” was white-knuckle terrifying, like driving through a carwash. No lines visible on the side of the road. Can’t we get these windshield wipers to go any faster? We hitched our star to an emergency vehicle right in front of us and could make out his rear lights well enough to just follow and pray. We'd go through bands of fifteen minutes and then get a break. Then back into it. After breaking into the "clear" in one stretch, a loud beep emanated from our phones announcing, "tornado alert -- seek cover immediately." There was nowhere to seek cover, but my husband moved into the left lane, and said "I just want you to know if there's a tornado, I'll steer us down into the ravine median since that's a low point. We're not out of control - that's our plan.” Us and the alligators, flashed through my mind. Fortunately, said tornado did not arrive. And three hours later, we swished our way to Miami. My husband was the inadvertent poster child for perseverance that night. He piloted us through three hours safely. Throughout the drive I could hear my granddaughter shouting at me, “Perseverance is not my best virtue!” During the summer I’d urged her to summon that excellence and keep swimming towards me across what to her seemed an impossibly long stretch of bay. She made it. A short swim. Like our short drive. But now the real work of perseverance begins for so many. Starting from scratch. Rebuilding. Summoning reserves of resolve, diligence, and hope. Staying focused for the long haul as we work to restore homes, businesses, and lives. It’s hard to persevere when life has become a mucky slog, rather than a terrifying adventure.  For many, it’s about waiting an hour in their overheated cars in ninety degree weather as they queue up for food. Yesterday, in one part of Naples, Our Daily Bread, Al’s Pals, and the Salvation Army gave out more than 300 free meals, bags of food, and grocery store gift certificates for families ranging from two to ten people. Families who’d lost their homes, their livelihoods. Many of them had English as their second language. The lines stretched out the high school parking lot and moved at a snail’s pace. But people waited and received with gratitude and good grace. I have had stellar examples of perseverance in my life. My mother was a prisoner of war during World War II, and for three years endured captivity, disease, cruelty, and starvation in a Japanese internment camp in Manila. She was full of stories about enduring and outwitting hunger (she kept a recipe book) and boredom (though study and shows), surviving diphtheria and beriberi, and occasionally outwitting their captors. She weighed ninety pounds when liberated and stood 5’4. In 2015 I attended a seventieth anniversary event for the liberation of the camp, and a high school student asked one of the surviving internees (then in her late 80s) whether she or others had been tempted to suicide in the face of such a struggle. The girl admitted that she herself sometimes had suicidal thoughts and had endured no such tragedy. Mrs. Bennett looked surprised at the question. “No, no, we didn’t,” she said. “I don’t know anyone who thought of suicide. We had each other and we never lost hope. We knew, we just knew our boys would come and liberate us.” And they did. Perseverance is not a flashy virtue. It's about putting one foot in front of the other again and again -- hour after hour, day after day, and sometimes year after year. But, as Joan Bennett reminded us, perseverance is closely related to hope. And friends along the way. Barry had the hope of finding his family and the companionship of Cruz. Internees had the hope of freedom and the unfailing support of each other. The Hispanic and Haitian-born Naples needy have the perennial hope of the American dream, a better life in this new country they’ve adopted, and they’ve got the help of each other, along with volunteers and organizations who roll up their sleeves and say “we’re all in this together.” So, to quote a sage, “let us persevere in running the race that lies before us.” Mary Beth Klee Naples, Florida To contribute to Florida disaster relief, your help is needed at https://www.volunteerflorida.org/donatefdf/ To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |