Heroes - Lives to Learn From

December

Generosity Charity Service

December

Generosity Charity Service

William and Catherine Booth - Service

Founders of the Salvation Army, William and Catherine Booth were both born in England in 1829 and married in 1855. William was an inspired and enthusiastic preacher, while Catherine was a thoughtful, sensitive woman who was said to have read the whole Bible eight times before the age of 12. As their ministry to others began, they felt a calling to serve those who were traditionally left behind by society: the poor, homeless, and alcohol-addicted of the London streets. By 1867, the Booths had ten full time workers in London's East End, a thousand volunteers, and 42 evangelists whose mission was both spreading the gospel and generous service to the most vulnerable. Booth himself dubbed them a "Salvation Army," and people began referring to William as "the General" and Catherine as "Army Mother." Both worked tirelessly to serve their flock. A quarter of a million of London's poor became enthusiastic members of their fold between 1881 and 1885.

The movement journeyed to the United States in the hands of a seventeen-year-old girl, Eliza Shirley, whose parents were moving to America but who was passionate about the Salvation Army's mission.

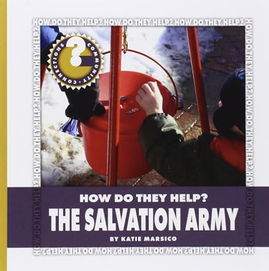

Today, the Salvation Army is the largest non-governmental social services provider in the United States, and one of the largest in the world. The Salvation Army's charitable services include rehabilitation centers, thrift stores, hospitals, after school programs, food pantries, homeless hostels, children's homes, mother and baby homes, and homes for the elderly. At this time of year, the Salvation Army's most famous fundraiser is their "bell ringer" program, where volunteers ring bells to help support their many ministries and donors leave money in their "red kettles."

Founders of the Salvation Army, William and Catherine Booth were both born in England in 1829 and married in 1855. William was an inspired and enthusiastic preacher, while Catherine was a thoughtful, sensitive woman who was said to have read the whole Bible eight times before the age of 12. As their ministry to others began, they felt a calling to serve those who were traditionally left behind by society: the poor, homeless, and alcohol-addicted of the London streets. By 1867, the Booths had ten full time workers in London's East End, a thousand volunteers, and 42 evangelists whose mission was both spreading the gospel and generous service to the most vulnerable. Booth himself dubbed them a "Salvation Army," and people began referring to William as "the General" and Catherine as "Army Mother." Both worked tirelessly to serve their flock. A quarter of a million of London's poor became enthusiastic members of their fold between 1881 and 1885.

The movement journeyed to the United States in the hands of a seventeen-year-old girl, Eliza Shirley, whose parents were moving to America but who was passionate about the Salvation Army's mission.

Today, the Salvation Army is the largest non-governmental social services provider in the United States, and one of the largest in the world. The Salvation Army's charitable services include rehabilitation centers, thrift stores, hospitals, after school programs, food pantries, homeless hostels, children's homes, mother and baby homes, and homes for the elderly. At this time of year, the Salvation Army's most famous fundraiser is their "bell ringer" program, where volunteers ring bells to help support their many ministries and donors leave money in their "red kettles."

The Hallelujah Lass: A Story Based on the Life of the Young Salvation Army Pioneer Eliza Shirley. Wendy Lawton. Moody Publishers, 2004. (5-7) Service, Generosity, Charity.

A slim chapter book about the life of Eliza Shirley, who traveled from England at 16 with the fire of charity in her heart to spread the word of the Salvation Army to the United States. Eliza faced challenges both from William Booth himself, who did not fully approve of her journey, and from unsympathetic audiences in the States—but her work paid off and now the Salvation Army is the largest non-government provider of social services in America. |

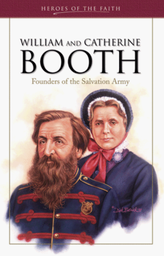

William and Catherine Booth: Founders of the Salvation Army. Helen K. Hosier. Barbour Publishing, 1999. (7-8) Service, Generosity, Charity.

This biography for older children and adults tells the story of William and Catherine Booth's founding of the Salvation Army despite the challenges and opposition they faced along the way. Emphasizes the sacrifices the Booths made in order to bring their charitable work to life. |

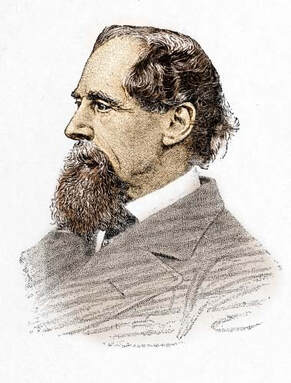

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) - Charity

"I have always thought of Christmas time ... as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of in the long calendar year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely and to think of people below them as if they were really fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.“

So proclaims Scrooge's nephew Fred as he ponders the hopelessly hardened heart of his miser uncle in Charles Dickens' classic, A Christmas Carol. A concern for the “least among us” pervaded Dickens' life and suffused his novels. It shines with particular clarity in “A Christmas Carol," beloved by generations during the holiday season for nearly 180 years.

Charles Dickens grew up in industrializing London of the early nineteenth century. As a young boy, he knew both well-being and poverty. When his spend-thrift father ended up in debtor’s prison, so did the rest of the family – except Charles. Twelve-year-old Charles was sent into the London workforce and labored ten hour days at a shoe blacking factory to help make ends meet. ("Are there no workhouses?" demands Scrooge when asked for a donation for the poor.) Dickens never forgot the degrading conditions and the scorn for the poor that he experienced. He also came to know first-hand the crime-ridden life in London’s slums.

Later, Charles was fortunate enough to be left a modest inheritance by his paternal grandmother, and receive an education. But his concern for the impoverished, for those who lived in his city’s bleak slums never left him. He fought for the poor and abandoned with what became his sharpest weapon – the pen. His novels, from Oliver Twist (1839) to Great Expectations (1861) artfully memorialized many of the characters and situations he had lived as a boy. Some of his books were responsible for legislation and action to improve conditions for the poor. As a father, here is the prayer he penned for his children.

"Make me kind to my nurses and servants, and to all beggars and poor people…charitable and gentle to all.”

The lesson of Charles Dickens’ life for children is indeed a Christmas carol: that generosity, charity, and service can be practiced in many ways – and should depend on one’s talents. Some may go into the slums and attempt to improve lives through better education, housing, or nutrition. Others may donate funds. Still others should pick up their pens. But all should be attentive to the needs of fellow passengers on the journey of life. To that end, we can think of no better hero than Dickens (we feature two picture book biographies below) and no better work this month than A Christmas Carol.

The splendid unabridged original can be read profitably at grades 4-8 and of course into adulthood! We've also featured some delightfully written (and not quite so scary) adaptations for young children.

"I have always thought of Christmas time ... as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of in the long calendar year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely and to think of people below them as if they were really fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.“

So proclaims Scrooge's nephew Fred as he ponders the hopelessly hardened heart of his miser uncle in Charles Dickens' classic, A Christmas Carol. A concern for the “least among us” pervaded Dickens' life and suffused his novels. It shines with particular clarity in “A Christmas Carol," beloved by generations during the holiday season for nearly 180 years.

Charles Dickens grew up in industrializing London of the early nineteenth century. As a young boy, he knew both well-being and poverty. When his spend-thrift father ended up in debtor’s prison, so did the rest of the family – except Charles. Twelve-year-old Charles was sent into the London workforce and labored ten hour days at a shoe blacking factory to help make ends meet. ("Are there no workhouses?" demands Scrooge when asked for a donation for the poor.) Dickens never forgot the degrading conditions and the scorn for the poor that he experienced. He also came to know first-hand the crime-ridden life in London’s slums.

Later, Charles was fortunate enough to be left a modest inheritance by his paternal grandmother, and receive an education. But his concern for the impoverished, for those who lived in his city’s bleak slums never left him. He fought for the poor and abandoned with what became his sharpest weapon – the pen. His novels, from Oliver Twist (1839) to Great Expectations (1861) artfully memorialized many of the characters and situations he had lived as a boy. Some of his books were responsible for legislation and action to improve conditions for the poor. As a father, here is the prayer he penned for his children.

"Make me kind to my nurses and servants, and to all beggars and poor people…charitable and gentle to all.”

The lesson of Charles Dickens’ life for children is indeed a Christmas carol: that generosity, charity, and service can be practiced in many ways – and should depend on one’s talents. Some may go into the slums and attempt to improve lives through better education, housing, or nutrition. Others may donate funds. Still others should pick up their pens. But all should be attentive to the needs of fellow passengers on the journey of life. To that end, we can think of no better hero than Dickens (we feature two picture book biographies below) and no better work this month than A Christmas Carol.

The splendid unabridged original can be read profitably at grades 4-8 and of course into adulthood! We've also featured some delightfully written (and not quite so scary) adaptations for young children.

A Christmas Carol. Retold by Tony Mitton. Illustrated by Mike Redman. Orchard Books, 2020. (K-2)

A charming poetic adaptation to delight the youngest of our students.

A Christmas Carol. Charles Dickens. Retold by Adam McKeown. Illustrated by Gerald Kelley. Doubleday Books, 2015. (2-4).

A fine retelling for children ready for a meatier story, but not the length or sophistication of the Dickens original.

A Christmas Carol. Charles Dickens. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Calla Editions, 2018.

The splendid unabridged original with exquisite pen and ink illustrations.

A Christmas Carol (Deluxe Library Binding) Charles Dickens. Illustrated by Charles Dana Gibson.Engage Classics, 2020 (4-8)

The splendid unabridged original with illustrations by the incomparable Charles Dana.

A Christmas Carol.* Charles Dickens. Illustrated by Roberto Innocenti. Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 1990. *Available on Epic!

This unabridged version with its engaging illustrations is available online. |

A Christmas Carol: An Engaging Visual Journey. (4-8) Charles Dickens. Illustrated by Jill De Haan. Tyndale House, 2021.

The splendid unabridged original with marvelous illustrations.

The Illustrated Christmas Carol. 200th Anniversary Edition. Charles Dickens. Illustrated by Frederick Coburn and George Alfred Williams. Seawolf Press, 2020. (4-8)

The splendid unabridged original with haunting pencil illustrations.

A Christmas Carol. * Charles Dickens.

Illustrated by John Leech. Tole Publishing, 2019. (4-8) Generosity, Service Miserly, self-centered Scrooge learns to look beyond himself and his own well-being, when Christmas Eve affords him the opportunity to revisit his past, present, and peek ahead to his grim future if his life is unchanged. This unabridged version of Dickens’ classic tale weaves timeless text with outstanding illustration. The combination of Dickens poignant story and Leech’s Rembrandt-like illustrations make this the perfect holiday read-aloud for the older grades.*Available on Epic!

Charles Dickens: Scenes From an Extraordinary Life

Mick Manning and Brita Granstrom. Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, 2011 (K-3) An excellent young child's introduction to the life of Charles Dickens.

Charles Dickens: The Man Who Had Great Expectations

Diane Stanley and Peter Vennema. Illustrated by Diane Stanley. Morrow Junior Books, 1993. (4-6) Another Diane Stanley triumph with this biography for older children. |

Generosity - Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919)

"The man who dies ... rich, dies disgraced." Scottish immigrant, steel magnate, and one of America's wealthiest men, Andrew Carnegie believed in giving back. Carnegie and his family came to the United States from Scotland in 1848. The family struggled, but twelve-year-old Andrew was industrious and highly motivated. He worked his way from "bobbin boy" at a local cotton mill in Pennsylvania to telegraph operator for the railroads to investor in steel and then Industrial Titan. Carnegie pioneered steel mills and eventually controlled the all important late nineteenth steel industry.

He made a fortune, but did not seek immense wealth for personal use. He had a strong sense of civic duty and in his "Gospel of Wealth," urged all who had been blessed with riches to spend them on behalf of others. (His employees wish he had spread more of his wealth to them!) He became America's most renowned philanthropist, eventually giving away more than $350,000,000 (that's billions in today's dollars). Carnegie wanted the doors of knowledge open to all, and he specialized in founding libraries (2,509 libraries!) across the country. But in addition, he funded Carnegie Hall, Carnegie Mellon University, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institute for Science, and the Carnegie Hero Fund. The medal he designed to award to his own heroes (named by the Carnegie Hero Fund) bore the inscription of John 15:13 on the outer edge: "Greater love hath no man than this: that a man lay down his life for his friends."

(Portrait From the National Portrait Gallery by an unidentified artist.)

"The man who dies ... rich, dies disgraced." Scottish immigrant, steel magnate, and one of America's wealthiest men, Andrew Carnegie believed in giving back. Carnegie and his family came to the United States from Scotland in 1848. The family struggled, but twelve-year-old Andrew was industrious and highly motivated. He worked his way from "bobbin boy" at a local cotton mill in Pennsylvania to telegraph operator for the railroads to investor in steel and then Industrial Titan. Carnegie pioneered steel mills and eventually controlled the all important late nineteenth steel industry.

He made a fortune, but did not seek immense wealth for personal use. He had a strong sense of civic duty and in his "Gospel of Wealth," urged all who had been blessed with riches to spend them on behalf of others. (His employees wish he had spread more of his wealth to them!) He became America's most renowned philanthropist, eventually giving away more than $350,000,000 (that's billions in today's dollars). Carnegie wanted the doors of knowledge open to all, and he specialized in founding libraries (2,509 libraries!) across the country. But in addition, he funded Carnegie Hall, Carnegie Mellon University, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institute for Science, and the Carnegie Hero Fund. The medal he designed to award to his own heroes (named by the Carnegie Hero Fund) bore the inscription of John 15:13 on the outer edge: "Greater love hath no man than this: that a man lay down his life for his friends."

(Portrait From the National Portrait Gallery by an unidentified artist.)

Andrew Carnegie. Builder of Libraries. Charnan Simon.

Children's Press, 1997. (3-4)

Life Skills Biographies: Andrew Carnegie.* Sarah DeCuapaw.

Cherry Lake Publishing, 2007. (4-8) *Available on Epic! |

The Man Who Loved Libraries*Andrew Lawson.

Illustrated by Katty Maurey. Owlkids, 2017. (K-3) A simple introduction to the life of steel titan Andrew Carnegie, who began life in the as a poor immigrant, and became one of America’s wealthiest men. He believed that “he who dies rich, dies disgraced.” Emphasizes his life-long love of libraries as repositories of learning and his desire to make their riches accessible to those in need. *Available on Epic! |

Jane Addams, by George de Forest Brush

Jane Addams, by George de Forest Brush

Service - Jane Addams (1860 -1935)

"The good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain...

until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into our common life."

So wrote Jane Addams in her classic work Twenty Years at Hull House. Jane Addams pre-dated Mother Teresa by half a century, but she was nothing short of America's own servant of the poor. She was born to privilege, but from an early age felt a sense of responsibility for helping those in need. A carriage ride with her father at age six opened her eyes to the appalling living conditions of Chicago immigrants. She told her father she would buy the finest house in that neighborhood to live among them, understand their problems and help them.

Her life's work became just that: serving the large immigrant community-- Italian, Polish, German and Russian -- in Chicago's industrial district. In 1889 at Hull House, a restored mansion in the heart of a multi-ethnic neighborhood, she and other residents worked to meet their needs and offer social and educational opportunities. Hull House residents offered everything from babysitting, to English classes, to meals, classes on nutrition, sanitation, sewing, bookbinding, concerts, discussion groups. They provided medical help and shelter for victims of domestic abuse. The "settlement house" movement in America began with Jane Addams, but by 1920 there were more than 500 such homes in major American cities serving the large urban immigrant communities, and helping them make it in their new home.

The life of Jane Addams reminds us that we are called to serve each other, and that in a democracy, we are all in it together. Jane was fond of saying "the cure for the ills of democracy is more democracy," by which she meant more people helping people. How? "By mixing on the thronged and common road where all must turn out for one another, and at least see the size of one another's burdens." (Democracy and Social Ethics)

"The good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain...

until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into our common life."

So wrote Jane Addams in her classic work Twenty Years at Hull House. Jane Addams pre-dated Mother Teresa by half a century, but she was nothing short of America's own servant of the poor. She was born to privilege, but from an early age felt a sense of responsibility for helping those in need. A carriage ride with her father at age six opened her eyes to the appalling living conditions of Chicago immigrants. She told her father she would buy the finest house in that neighborhood to live among them, understand their problems and help them.

Her life's work became just that: serving the large immigrant community-- Italian, Polish, German and Russian -- in Chicago's industrial district. In 1889 at Hull House, a restored mansion in the heart of a multi-ethnic neighborhood, she and other residents worked to meet their needs and offer social and educational opportunities. Hull House residents offered everything from babysitting, to English classes, to meals, classes on nutrition, sanitation, sewing, bookbinding, concerts, discussion groups. They provided medical help and shelter for victims of domestic abuse. The "settlement house" movement in America began with Jane Addams, but by 1920 there were more than 500 such homes in major American cities serving the large urban immigrant communities, and helping them make it in their new home.

The life of Jane Addams reminds us that we are called to serve each other, and that in a democracy, we are all in it together. Jane was fond of saying "the cure for the ills of democracy is more democracy," by which she meant more people helping people. How? "By mixing on the thronged and common road where all must turn out for one another, and at least see the size of one another's burdens." (Democracy and Social Ethics)

Dangerous Jane.* Suzanne Slade. Illustrated by Alice Ratterree. Peachtree Publishing, 2017. (2-5) Service, Compassion, Mercy, Courage

The first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize, Jane Addams had a heart for those in need. She lost her mother at age two and endured a debilitating disease as a child. Her father made sure Jane read deeply and was not insulated from the needs of others. Early on, the little girl wondered what she could do to help those in her city who suffered poverty and injustice. As a young woman, she started Chicago's Hull House to assist the immigrant community. She was a study in courage as she continued to take strong stands on hard issues (World War I) and faced lots of public criticism. This is a powerful biography of her life, poetically written and illustrated with evocative water color pen and ink drawings. *Available on Epic!

Jane Addams: Pioneer Social Worker. Charnan Simon. Children’s Press, 1998. (3-6)

An amply illustrated presentation of the civic heroine, Jane Addams, who was devoted to helping those in need. This third to sixth grade treatment introduces young readers to the remarkable woman who founded Chicago’s Hull House, aiding immigrants and other laborers through education, day care for their children, self-help clubs and even an introduction to American art and culture. |

The House that Jane Built: A Story about Jane Addams.* Tanya Lee Stone. Illustrated by Kathryn Brown. Henry Holt & Co, 2015. (K-4) Service, Generosity, Hospitality Compassion

Why would a wealthy young woman forsake a life of privilege and pour her resources and herself into opening a home for Chicago's newest immigrant arrivals? Because even as a young child, Jane had eyes to see those in need, and a desire to serve them. This is an inspiring, beautifully written portrayal of the life of Jane Addams, founder of Hull House, which served Chicago’s destitute and immigrant communities at the turn of the century. Muted watercolors perfectly portray the period. *This story is available on Storyline Online.

Jane Addams: Champion of Democracy. Dennis Brindell Fradin and Judith Bloom Fradin. Clarion, 2006. (5-6)

This young adult biography introduces students to the tireless and resourceful civic heroine, Jane Addams (1860-1935), whose life was devoted to helping others realize the American promises of opportunity and possibility. She is primarily remembered for her work to aid immigrants with the establishment of Hull House in Chicago. She also advocated for women’s suffrage and then civil rights (helping to found the NAACP), and worked for international peace in the early twentieth century, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935. |