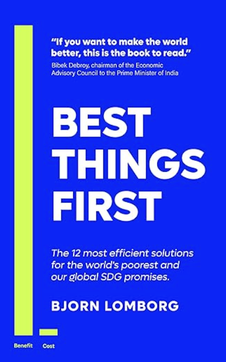

Janus, for whom the month of January is named, is the Roman god who has one face staring backward and another peering forward. He is a great metaphor for this month, having ended one chapter even as we open another. Some images of Janus show the backward-looking visage as bearded and horned, while forward-facing Janus is clean-shaven and smooth cheeked. Backward-facing Janus scowls at the weight of the past. Forward-looking Janus smiles: he’s a youth with the added wisdom of experience literally behind him. He’s ready to GO FORTH ON GOOD PATHS. My candidate for the Janus Award this January, a just-now designed award for intellectual courage and common sense, is Bjorn Lomborg. The Danish economist looks the part. He is smooth-cheeked and perennially boyish, though next year he will turn 60 (with wisdom of the past behind him). Throughout his career, he has specialized in clear-eyed and unexpected thinking, championing workable solutions to thorny issues with buoyant enthusiasm. But Lomborg’s most recent book, Best Things First, is arguably his finest. In it he proposes the twelve most efficient solutions for aiding the world’s poorest, and for fulfilling the UN’s very ambitious sustainable development goals (SDG). A little background: in 2012 (pre-pandemic Eden and buoyed by progress made in meeting eight UN Millennium Development Goals) UN teams took up a new task: deciding goals to be met by 2030. These were dubbed “Sustainable Development Goals.” Rather than replicate the successful Millennium model of specific targeted goals, world leaders came up with seventeen major rubrics and 169 total goals that promised numerous wonders by 2030: the eradication of poverty, hunger, and disease. An end to war, a halt to climate change. The advance of education and the abundance of clean water. Gender equality. The extirpation of corruption and the end of food waste. And many more. Organizational psychologists insist that if you have more than three priorities, you have none—so this was problematic. Then came the pandemic—which affected all of us, but devastated those most in need. African nations fell further behind than ever before.  In his most recent book Bjorn Lomborg looks back at how we got here, and then reflects on the fact that we are not even close to meeting the new Sustainable Development Goals. But we could get much closer much faster and for a very reasonable amount of money, he argues. “Our goal is to pinpoint where we can create the most value for humanity per dollar, rupee, or shilling spent.” Where is the biggest bang for our buck? Lomborg leads off with a clear-eyed observation: “We all want a better world. Unfortunately, our efforts are often hampered by wanting to achieve not just some but all good things, at once, many of which are nearly impossible, prohibitively expensive, or terribly inefficient, or all these things at once. So this book outlines how to do the best things first.” His twelve “best things” solutions (each a chapter) target tuberculosis, maternal and newborn health, malaria, nutrition, chronic disease, childhood immunization, education, agricultural R&D, e-procurement, land tenure security, trade and skilled migration. In twelve peer-reviewed, data-rich studies he concludes that if the world spent $35 billion dollars yearly —which is about the amount that we spend on cosmetics—we could dramatically improve the lives of the world’s poorest. Compare this with “it takes trillions” annually to solve climate change. (John Kerry)  Bjørn Lomborg Bjørn Lomborg Lomborg estimates that for that amount “we can save 4.2 million lives annually, and we can make the poorer half of the world more than a trillion dollars better off each and every year. We can almost entirely end tuberculosis, which needlessly kills more than a million people each year. We can reduce the death toll of chronic diseases by 1.5 million… We can increase yields in agriculture, making farmers produce more, consumers pay less, while avoiding hunger for more than a hundred million people. And we can ensure almost every kid in the poorer half of the world actually learns while they’re in school, thus raising these children’s eventual incomes collectively by more than $600 billion per year. In short we can achieve a vast amount while spending relatively little.” While chock full of data, the book is very readable. Lomborg intends it for policy makers and philanthropists and for all people of good will who are looking for concrete ways to make a difference. “Please pick one of these twelve areas for your coming investments,” Lomborg urges. Those investments can be investments of time and attention too – particularly as we ask students to think about creating a better world. It’s not all about recycling. It takes intellectual courage to promote solutions that are at once simple and effective, but outside the mainstream view of immediate imperatives. It would be easier to champion trillions for climate change. Still, Lomborg is making inroads. We can’t do everything at once, he cautions the UN. Let’s do the best things first. The endorsement of his work is coming from sources as diverse as Bill Gates, Larry Summers, Jordan Peterson, Terrence Keeley, and international development officers worldwide. Now, if we could just start charging forward on these good paths… That’ll take courage. Mary Beth Klee

1 Comment

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |