|

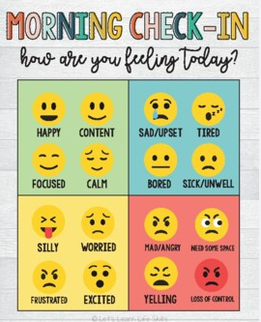

“The Morning Check-In is the heart of the day.” When I read those words recently on a Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) website, I did a double-take. Since 1992, the Core Virtues program has proudly proclaimed “The Morning Gathering is the heart of the day.” It’s all over our website. By “Morning Gathering” we refer to a K-6 circle time meeting that celebrates a given virtue with a great story. In April, for example, the teacher reads an inspiring picture book like Me and Momma and Big John that shows an artisan (and her son) learning humility by seeing her work as part of something larger and more meaningful than personal statement.  Morning Gatherings are times for kids to leave behind whatever happened at home last night or at drop-off that morning, and to be drawn instead into a well-written story with intriguing characters who model courage, compassion, respect, or diligence. This is the “fill ‘er up!” time of the day. For fifteen minutes they are in a story where life is hard, but characters exercise moral excellence and find a way. Children are given hope. Then they turn to phonics or math inspired to do their best and be their best.  So, what are “Morning Check-Ins”? What’s the difference? It’s huge. The Morning Check-In in SEL programs generally involves taking the emotional temperature of the class -- individually. Teachers invite students to begin the day by reflecting on how they are feeling. Frequently used posters feature at least sixteen facial emojis that invite children to reflect on whether they are happy, content, focused, and calm, or twelve other choices such as sad/upset, tired, bored, sick, silly, worried, frustrated, excited, mad/angry, need some space, yelling, or out of control. Teachers employ these posters in different ways, but enthusiastically note in their reviews: “I use their choices to guide our morning meetings.” In other words, take time to reflect on what’s troubling or exciting them - and there are lots of possibilities. “I like to use this in the morning and after recess to see how my students are feeling,” one teacher writes. In other words: ask them to focus on their feelings at least twice a day.  What’s wrong with this picture? Abigail Shrier can tell you. The Wall Street Journal investigative reporter’s new book, Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up, has a lot to say about our current counter-productive tendency to focus on emotions. It is “airborne” in our culture and in our parenting, and is being encouraged in schools across the country. And it's debilitating. Starting from the statistically proven observation that “we have raised the loneliest, most anxious, depressed, pessimistic, helpless, and fearful generation on record,” Shrier asks “why?” She documents a widespread “culture of therapy” in modern America, which emanated originally from the mental health community. In the past two decades it has infiltrated schools and is causing “iatrogenic” harm - unintentional harm caused by the healer. Shrier asserts that in education many of these therapeutic practices (which she describes as "social and emotional meddling") are eating into childhood resilience. They induce an unhealthy focus on the least reliable of our moral and mental health indicators: emotions. As one who has watched SEL programs bloom and proliferate over the years, I know that most SEL practitioners are well intended, and SEL schools promote goals that appear to echo aspects of virtues-based character education. Their stated goals — promoting safe and caring classroom environments, helping students develop “self-management,” navigate social situations, make responsible decisions, and cultivate “empathy” and “community participation” – sound very much like Core Virtues’ focus on respect and responsibility in schools, diligence and self-control, compassion for others and community service. The verbiage in SEL programs at times overlaps with verbiage in virtues-based education. But the pedagogy is worlds apart and the results are too. SEL programs turn the student inward. Their standards and competencies include self-determination, self-regulation, self-management, self-care, self-awareness, and self-talk. They attempt to balance these against social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. Through an elaborate schema intended to integrate all aspects of school life, they convey to the student: Mindfully consider your own state of being and emotions in the present moment.  Initially developed to improve the academic performance of troubled inner-city youth, SEL programs have morphed. They currently promote a lot of counter-productive interior analysis and rumination. What is rumination? It is the tendency to mentally review and constantly rehash past injuries and the ways in which things have gone or could go wrong in a given situation, to focus on possible obstacles impeding forward movement. Shrier has gleaned insights from many psychiatrists and psychologists. She points out that by constantly asking children to focus on their feelings, one is very likely to reinforce negative emotions in children afflicted by them. And not just that - we are likely to introduce negative emotions to children who hadn’t considered them. Let’s see: am I a little off today? Yes, I guess I should focus on that. This “emotional state” orientation instead of “action” orientation impedes growth and maturity. By asking kids to focus on their feelings, we often cripple them. “Academic psychologists note that people who adopt an ‘action orientation’ are able to focus on a task without getting distracted by thoughts about their current emotional or physical state,” Shrier writes. “Those who adopt a ‘state orientation’ on the other hand, are thinking more about themselves in the moment: how prepared they feel, that crick blossoming in their neck, the email they haven’t answered. Unsurprisingly, an action orientation makes it much more likely that you actually accomplish the task.” Michael Linden, MD, expert on mood disorders and professor of Psychiatry in Berlin, notes: “State orientation keeps you from being successful in anything.” Psychiatrists who treat patients crippled by emotional disorders often advise thinking LESS about one’s emotions. Shrier reminds us, “No winning head coach asks his players to dwell on their feelings at halftime. Instead of constantly asking kids to name how they feel in the moment, adults should be telling kids how imperfect and unreliable their emotions can be … that they sometimes deserve to be ignored. Healthy emotional life involves a certain amount of repression,” she writes in a recent Wall Street Journal (March 8) editorial. Abigail Shrier is not going to make a lot of friends by suggesting the importance of repression, but we all know that she is right. The times in our lives when we have accomplished the most meaningful goals are probably those in which we were somewhat anxious and stressed, but denied the emotion of fear’s power over us, exercising courage. Courage, the Core Virtues program defines as “moving beyond fear to venture and persevere.” Venturing and persevering is key. Why is Morning Gathering the heart of the day in Core Virtues programs? Because it provides imaginative fuel for noble action. It inspires hope. On a regular basis children are encouraged to look not in and down, but up and out. Treated to stories of boys and girls, men and women, sometimes dogs, cats, bunnies, mice, and hedgehogs, encountering difficult situations, kids identify with attractive characters who move beyond fear or crippling love of self to act heroically. They encounter great models. Plato reminded us that the purpose of stories is to help students fall in love with virtue, the excellences required of mature and fruitful adults. So, let’s help the kids grow up. Leave rumination behind; make sure these literature-based Morning Gatherings provide all-important moments of hope and inspiration. Mary Beth Klee

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |