|

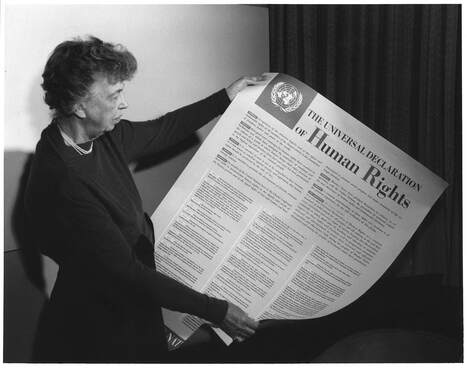

"If we do not lay ourselves out in the service of mankind, whom should we serve?” Abigail Adams (September 29, 1778) This December, as the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights turns 75, we do well to reflect not just on the document, but on the woman whose service to humanity made the work possible. Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady and widow of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, chaired the drafting committee for the landmark document. After two years of work, she secured consensus for this pathbreaking text among a committee that included Western philosophers and Confucian advocates. She mustered unopposed adoption of the document by the General Assembly of 58 nations. This was a gargantuan task, undertaken with perseverance, finesse, a spirit of service and yes, hospitality. But let’s look back. As a shy and insecure child who lost both parents by age 10, curious, idealistic Eleanor Roosevelt developed a heart for others. Her involvement with social causes predated her marriage to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and contributed to her unique and active embrace of the role of First Lady. From the time FDR was elected in 1932 promising a “New Deal” for suffering Americans, Eleanor traveled the United States, learning firsthand about the plight of the most afflicted. Whether miners, World War I veterans, laborers, African-Americans, impoverished children, or the disabled, First Lady Eleanor gave voice to their needs. She did this by regularly informing her husband, but also through her daily “My Day” newspaper column, her weekly CBS radio show, her monthly "If You Ask Me" magazine column in the Ladies Home Journal, and her regularly scheduled press conferences -- open only to women reporters. (Eleanor had observed that without that stricture, news outlets sent only men).  In 1936, the First Lady’s hospitality was extended to the stunning contralto Marian Anderson, who was asked to perform at the White House. She was African-American and that raised eyebrows. Three years later, when the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow Anderson to perform at their 4000-seat Constitution Hall venue, Eleanor resigned from the organization. She arranged for the artist to perform at the Lincoln Memorial in a landmark concert that moved hearts and lifted spirits on the eve of war. Seventy-five thousand (not four thousand) were in the audience. (Video of the concert here.) During World War II Eleanor wanted to serve troops suffering the hardships of war. She went to the frontlines in the Pacific theater, visiting hospitals and soldiers in Guadalcanal, holding plasma for doctors doing triage, walking more than fifty miles of corridors in a single day, and carrying in her pocket a prayer that said “Lord, lest I continue in my complacent ways, help me to remember that somewhere someone died for me today.” When Franklin died in 1945, Eleanor mourned and wondered what momentum her efforts might have without him. But she did not think her service to her country should die with him. After a brief withdrawal from politics, Eleanor returned to the public sphere, traveling the country and speaking out on public affairs. Harry Truman, who succeeded FDR, found Eleanor annoyingly critical of his implementation of the New Deal. Mrs. Roosevelt was beloved, listened to, and consistently audible/visible. She had persuasive powers.  Hmmm.... Why not ask Mrs. Roosevelt to head the US delegation to the new United Nations? Rumor had it that they were struggling to draft a universal declaration of human rights, an almost impossible task given the roster of nations, which included the Soviet bloc, apartheid South Africa, and restrictive Saudi Arabia. The meetings for that work would be largely in Europe, moving Eleanor overseas. To Truman’s great delight and to the chagrin of the entirely male US delegation, Eleanor accepted. Her work in the next two years as Chair of the drafting committee for a new Universal Declaration of Human Rights was arguably Eleanor's greatest contribution to public life. She was gifted not simply in devotion to principle and ideals, but in understanding the thoughts and needs of others. Fluent in five languages, she knew the importance of making others (especially one’s guests) feel at home. She treated her collaborators on this project as her guests, and they often were. Eleanor believed in conversation. Dinner parties, informal meetings, and one-on-one conversations were her forte. Biographer Allida Black notes that in the last sixty days before the hard-fought document went to a vote before the General Assembly, Mrs. Roosevelt held (and attended) 85 working sessions in sixty days, and more than a hundred individual meetings with members of the General Assembly or their staff on top of those 85. Though several nations abstained, the document was approved without opposition by the General Assembly on December 10, 1948. On the heels of atrocities recently experienced in World War II and unfortunately ever-present in our world-- the preamble proclaimed: “Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind,” this declaration of shared principle was necessary. Article 1 featured pathbreaking language. “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Who had rights? ALL human beings – men, women, children. And a right to what?

All hail to Eleanor Roosevelt, a woman of hospitality and tireless service to humanity; and all hail to the vision enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Both provide a beacon of light in the darkness of our December nights. - Mary Beth Klee

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |