|

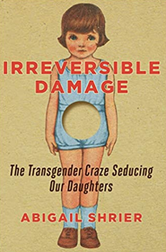

In March, Women’s History Month, we’re paying special attention to the challenges that young girls face growing into adult womanhood. Since 1987 our nation has celebrated “Women’s History Month.” That decision (a Congressional resolution) came on the heels of a 1970s feminist revolution aimed at opening for women any career path they chose and any future they deemed worthy. Let’s not stereotype women, was the message: women’s contributions need not be limited to home and family nurture; they have been and can be valuable contributors to economic and social wellbeing. The women’s movement of that era sought educational and professional opportunities equal to those offered men. Young women who came of age in the 1970s largely lived out those dreams and forged paths that would open doors for the next generation of women. In 1970, men outnumbered women at the university by 58 percent to 42%, but by 1980 the enrollment by sex was 50-50. Now women surpass men as a percentage. And career paths were unlimited: women became architects, astronomers, bankers, engineers, entrepreneurs, fighter pilots, etc. The Core Virtues Women’s History Month tab recommends numerous wonderful children’s biographies of the many trailblazers in those fields. And most of the women profiled, from Abigail Adams to Eleanor Roosevelt, were also proud to be wives, mothers, and homemakers. It would seem that with all this progress, there has never been a better time to be a woman.  A pioneering female student arrives at the University of Notre Dame in the 1970s. A pioneering female student arrives at the University of Notre Dame in the 1970s. But evidence from many sources suggests the opposite. Last month the Center for Disease Control (CDC) released data showing that teen girls “were engulfed in [a wave of] violence and trauma.” And we see that reflected in news stories. Online bullying incidents among girls have become toxic and tragic. Last month fourteen-year-old Adriana Kuch was savagely attacked by other teen girls in a New Jersey high school hallway. Bystander girls filmed the beating, then posted it on Tik Tok, with ongoing taunts about how she “deserved it.” Humiliated, ninety-eight-pound, five-foot-two Adriana, who loved animals and worked with special needs kids, committed suicide two days later. This is an extreme case with devastating consequences – but it is not isolated. Teen girls “beating up” on other teen girls via social media is now a national epidemic. For decades girls have been infamous for cliques that exclude those who are “not cool,” (satirized in the 2004 movie Mean Girls) but since 2007 “mean girls” have been armed with a new weapon: the smartphone. Amid screen-addicted friends, they spread shame, mockery, and self-doubt. No wonder the CDC finds that 57% of teen girls report themselves “persistently sad or hopeless,” and that 30% have considered suicide. Here's another alarming stat for the future of womanhood. One in five thirteen- to seventeen-year-olds are identifying as “transgender,” and the vast majority are pre-teen and teen girls who showed no sign of gender dysphoria (discomfort in the sex of their birth) in early childhood. What was once a rare psychiatric condition (until 2013 known as “gender identity disorder”) that manifested itself almost exclusively among pre-school boys who identified as girls--has become a social trend.  Girls as young as fifth grade are opting out of growing into adult womanhood. They cut their hair, change their name and pronouns, adopt male clothing, bind their breasts, and contemplate puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones, perhaps the eventual top surgery and phalloplasty. More than any other writer Wall Street Journal investigative reporter Abigail Shrier documented and analyzed this phenomenon of “rapid onset gender dysphoria” in her jaw-dropping 2020 book, Irreversible Damage: How the Transgender Craze is Seducing Our Daughters. She too found social media peer groups pushing this evolution and documents many of its long-term effects. These new developments bode ill for the future of womanhood. Girl-on-girl physical, emotional, and verbal abuse of the scale we are now seeing is new and frightening. It mirrors the behavior of fictional pre-teen boys in William Golding’s 1954 novel Lord of the Flies, in which cruelty, tribalism, and savagery come to characterize British boys stranded on a desert island. Typically, we did not associate this behavior with girls. And now young girls imagine themselves born into the wrong body and seek a new identity as males. Why are these behaviors developing among our girls? There are three answers: one psychological, one technological and the other cultural. Psychology first. Teens are a peer-driven group. This is the age at which young people seek to establish independence from parents, and strengthen their own identity and self-worth, often in tightly knit and trusted peer groups. Psychologists see this increased peer-group reliance as a not-necessarily-unhealthy step in emotional maturity. It is a way of both asserting young adult independence and acquiring emotional support by acceptance into a chosen group. Teen girls are particularly insatiable in their desire for peer group connection. When those peer groups are healthy (kids who are excited about learning, the arts, outdoor activities, sports, faith, or supportive of helping others) the experience is positive and a step in emotional maturity. When peer groups are power- and exclusion-driven (kids who see coolness in wealth, appearance, clothing, manner of speech, substance-use etc.) the experience can quickly become toxic. Such peer groups thrive on ostracism and the rising incidence of bullying in American middle and high schools attests to that. Throw into this mix our new twenty-first century companion: the smartphone, born as the “iPhone” in 2007. America’s parents have been reeling ever since. According to the Pew Research Center 88% of American teens own a smartphone (the average age of the adolescent user is 12-13), and as of 2019, 95% had access to one at home. 78% of teens check their phones at least every hour. 72% feel the urge to respond to their texts of phone notifications. 59% of parents think their teens have a smartphone addiction. On the surface, this tool of technology is morally neutral; it has the potential to connect, inform, and entertain us all. But the advent of social media has enabled online peer groups. We are seeing teen cyber-bullying, and in-group out-group exclusions on an unprecedented scale. Tik-tok, Snapchat, and many other apps have come vehicles for sharing mortifying photos, publishing cruel comments, and encouraging self-doubt and self-hatred particularly among young girls. Many teen girls live in fear of what will be said about them online--a forum they do not control. Other girls use social media to seek out a peer group that gives them both a unique identity and a support group. Count most of the newly trans teens among the latter. Vulnerable or just plain curious young girls find plenty of support online for ditching society’s and their parents’ expectations of them at the most basic level – their sex. Puberty for girls has always been challenging, involving physical pain and discomfort, emotional rollercoasters of mood swings, and a large dose of insecurity. And since the 1970s, we’ve been broadcasting loud and clear that on the other side of the puberty divide, men have the upper hand. Women have to be twice as good to compete. And women have the added “burden” of childbearing and home making. So, what could be more appealing than opting out of all that? Abigail Shrier’s book documents the near-universal phenomenon of these young girls’ deep involvement on social media forums that offer new and exciting peer groups. Trans peer groups advertise themselves as a new family, and even encourage teen distancing from their biological families, as they establish their new gender non-conforming identity. Again, often with tragic results. A recent case in Virginia led one fifteen-year-old girl to leave her family home and meet up with her “online family,” only to discover that she fled to the arms of human traffickers. Why are girls doing this? Because in the realm of culture we have an unfinished feminist revolution. The Core Virtues program highlights compassion, faithfulness, and mercy as March virtues. These are virtues for both sexes, but they have historically been most closely associated with women. The nineteenth century German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously held up the “eternal feminine” (ewig-weibliche) as the highest human ideal. “The eternal feminine draws us on high” were the words with which he closed his masterpiece Faust. That feminine ideal embodied such traits as beauty, truth, love, compassion, mercy and grace. It was embraced by American feminists Margaret Fuller and Edna Cheney. It’s no accident that our March Core Virtues “heroes” have been mostly “heroines” – Clara Barton, Anne Sullivan, Mother Teresa. Compassion, mercy, and grace are the qualities that have characterized not just significant social reformers, but also the familial pillars of our society -- good mothers. The 1970s feminist revolution (of which I was a part) broadcast the message: motherhood and homemaking is not the whole story. But often the subtext was: motherhood and homemaking are for those who can’t cut it in the “real” world of commerce, enterprise, or academia. Motherhood is a biological accident of nature, not a worthy aspiration. And please don’t tell me to be meek and mild. The message we have not sent our daughters in the last fifty years is:

I am taking a suggestion from Abigail Shrier’s closing chapter and asking that our March message to young women be: it’s great to be a girl. I’m proud to be she.

-Mary Beth Klee To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |