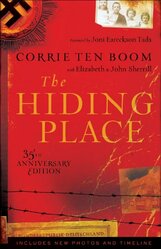

Corrie ten Boom’s particular push-come-to-shove moment came in 1947, when after addressing a Munich audience on forgiveness, she was approached by a former Ravensbruck prison guard. With horror, she recognized the guard who’d taunted and mocked her naked sister, as she was forced into the showers. He had "found Jesus," and was, she wrote, “beaming and bowing. ‘How grateful I am for your message, Fraulein,’ he said…his hand was thrust out to shake mine. And I, who had preached so often to the people … the need to forgive, kept my hand at my side. Even as the angry, vengeful thoughts boiled through me...I tried to smile, I struggled to raise my hand. I could not…I breathed a silent prayer. Jesus, I cannot forgive him. Give Your forgiveness. As I took his hand, the most incredible thing happened. From my shoulder along my arm and through my hand, a current seemed to pass from me to him, while into my heart sprang a love for this stranger that almost overwhelmed me.” Corrie spent the remaining thirty-five years of her life, putting that love into practice, establishing in the former Darmstadt concentration camp, a flower-filled, cheerfully painted place of renewal and rehabilitation for ex-prisoners and victims of war. Her 1971 book The Hiding Place and the 1975 film by the same name made her story known to a generation of readers and viewers.  Forgiveness on that level (like mercy) seems super-human and is often inspired by faith. Yet, it has been preached and practiced by pragmatic, not particularly religious people, like South Africa’s Nelson Mandela. He also had something to forgive. Actively resisting his country’s unjust apartheid regime, he organized armed struggle against the government and was jailed. Mandela spent twenty-seven years as a prisoner, much of it in solitary confinement, and endured torture and abuse. Yet he also had time to reflect, and come to know his enemy. When he was released, four years later becoming South Africa’s first black president, his principles were generosity of spirit and reconciliation; his politics were those of forgiveness. “I do not forget,” he said, “but I forgive... Forgiveness liberates the soul. It removes fear. That is why it is such a powerful weapon.” "We must strive to be moved by a generosity of spirit that will enable us to outgrow the hatred and conflicts of the past," the new president emphasized. The 2009 movie “Invictus” memorialized Mandela's first year as president, when in 1995 he threw his vigorous support behind South Africa’s mainly white Afrikaner rugby team, formerly a symbol of the hated apartheid regime. He urged them on to victory in the World Cup—an event that ended up uniting 43 million of his countrymen, fostering reconciliation and forgiveness like no other. Many contemporary psychologists emphasize forgiveness as a means of healing from a grave transgression – a coworker who has undermined you, a spouse who has betrayed you, a colleague who ensured your ouster, a “friend” who let his candid assessment of you poison a new relationship. Psychologists distinguish between forgiveness (desirable) and reconciliation (not always possible or desirable). The latter involves a restored relationship with the transgressor: the spouses, for example, are reconciled. Forgiveness, however, involves a psychological and emotional pivot that allows the person wronged to view the wrongdoer with compassion, kindness, and even to wish them well. Forgiveness, in other words, is a shift and a gift. Psychologists Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman define forgiveness as “an unconditional gift given to transgressors based on the belief in the innate value of all persons.” The person who practices forgiveness does not excuse the transgression, does not say “what you did is OK.” But he or she is able to let go of hurt, move beyond a desire for retribution, and toward an attitude first of forbearance and then of love. That is very hard. Divine even. One thinks, of course, of the font of Corrie ten Boom’s deep faith: Jesus on the cross, forgiving his crucifiers: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” Those words, which millions of believers will remember in a special way this month, have inspired and challenged generations of Christians. Nor are Christians alone in preaching forgiveness. Judaism teaches that God forgives people their sins, and commands them to forgive their transgressors. Islam refers to God as “Al-Ghafoor,” the Forgiving One, and encourages forgiveness in order to receive forgiveness from Allah. Buddhism and Hinduism enshrine the concepts of compassion and forbearance to encourage relinquishing one’s resentment towards the transgressor. What difference does it make? All the difference in the world. We all know people who have endured the same horrible experience, but have reacted in very different ways: one with bitterness and contempt, another with kindness and determination; one with resentment, another with forbearance; one with toxic rage, another with forgiving love. Which serves us better? Which is more attractive? Which is more liberating - for ourselves, our children, and our future? Corrie ten Boom made her choice. "Forgiveness is setting the prisoner free, only to find out the prisoner was me," she wrote. The greatest gift of forgiveness is for the giver. Corrie ten Boom was born and also died on April 15. It’s a good month to think about forgiveness. Mary Beth Klee To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |