|

For July 2024, we present an updated reflection from July 2020. July is usually our month of “huzzahs!” for independence and gratitude for the lazy days of summer. In Julys past, we’ve spotlighted the virtue of leisure -- rest for the human spirit -- in all its forms: seaside escapes and lake shore adventures, hikes through mountain and forest trails, family picnics and barbecues, outdoor concerts and sidewalk art exhibits, fireworks under the stars. And always, always, always… reading—drinking in the words and lives of strangers. American aphorist Mason Cooley put it well: “Reading gives us someplace to go, when we have to stay where we are.” Huzzah for magical transport. Read me away. Books open windows to worlds we know nothing about, but could visit and learn from.

Have you been to Nebraska in the late nineteenth century and met its German, Czech and Yankee settlers? Willa Cather’s My Antonia paints the exquisite beauty and loneliness of the landscape, the power of its changing seasons, and the captivating resilience of Great Plains settlers who forged a life there. Have you wondered if you’d be tough enough to leave your warring homeland and begin somewhere else? Read Isabel Allende’s triumph A Long Petal of the Sea, which chronicles a family fleeing Spain’s Civil War (1939) and making new lives in Chile. Are you curious about the Belgian Congo in the 1950s? (Aren’t we all?) Read Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible, and when you finish, you may weep that this fine book had to end. Are you seeking a first-hand account of justice gone wrong and forgiveness extended? Read Anthony Hinton’s spellbinding The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row -- an eye-popping account of an innocent black man sentenced to death in Alabama, who endured thirty years in prison before lady-justice removed her blindfold. If you just want some place new to go, and a fresh, funny take on it, try any of Bill Bryson’s travel books: I’m a Stranger Here Myself (Hanover NH), In a Sunburned Country (Australia) or A Walk in the Woods (Appalachian Trail). And, last of all, if you long for Christmas in July, don’t miss Gretchen Anthony’s hysterically funny and touching Evergreen Tidings from the Baumgartners, in which Violet Baumgartner, type-A matriarch from a distinguished family, channels her family’s (mis)adventures through the annual holiday letter. You’ll end up loving her. This summer, when so much of the news is dark and heavy and worrisome, take time to recharge and restore. Get above it. Read novels. Read poetry and more. And let Langston Hughes be your guide: So since I’m still here livin’ I guess I will live on. I could’ve died for love -- But for livin’ I was born. Though you may hear me holler, And you may see me cry – I’ll be dogged, sweet baby, If you gonna see me die. Life is fine! Fine as wine! Life is fine! P.S. If you’re looking for great reading for your kids, just peruse any of our month-related tabs and/or our chapter book section. And for our adult readers, we have a great new candidate for summer reading in 2024: Telling Our Stories, a "coffee break book" that is a print compilation of our best blog posts through the years. Get your copy here! See you in September…. Mary Beth Klee To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page.

0 Comments

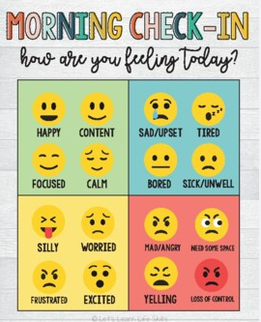

Our polarized times have a way of seeping into some of our most important and vulnerable institutions: public and private elementary schools. When topics such as critical race theory, gender identity, abortion, and climate change policy infiltrate K-6 classrooms, we have a recipe not for quality education, but for partisan indoctrination. Elementary school education is intended to be “elementary”—concerned with the basics, or in the definition of the Oxford dictionary, “straightforward and uncomplicated.” We should keep that in mind as we navigate these unsettled questions and their implications for K-6 schools. We do well to ask: what virtue should be uppermost in the minds of elementary school administrators and teachers who confront these issues on a curricular or programmatic level? The key is “stewardship.” We in K-6 education are first and foremost stewards for the education (and care) of the children in our schools. The Core Virtues program defines “stewardship” as “caring well for the gifts given us: our lives, our world, our talents, and those entrusted to our care.” Entrusted to the care of elementary schools are children. Minors. They are not miniature adults. They are full of curiosity, spirit, and often good will, but a child does not have a fully developed prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain which controls our highest cognitive abilities. Their emotions are more intense, volatile, and frequently expressed than adults. Children inhabit worlds that hover between fact and fantasy, rational and non-rational. Both of those worlds—the world of the empirical and the world of the imagination—are of supreme importance. The next generation of scientists and novelists, accountants and artists, mathematicians and ministers are in our classrooms. It is our responsibility to steward children with respect for their current state of development and also with respect for the diverse families who entrusted them to our care.  Strong academic programs like the Core Knowledge Sequence or the Hillsdale K-12 Program are ambitious, research-based programs that are respectful of a child’s state of development. They build sequentially and focus on the knowledge and critical thinking skills that need to be passed to the next generation for a bright future. What is an atom? How do we know they exist? What mathematical operations allowed the development of Google? Which poems have lifted hearts and minds? What are the major ancient civilizations? How is a republic different from an oligarchy? What are the major world religions and how are they alike and different? There is so much rich material to explore. And it’s not just factual. We are cultivating moral sensibilities – a love of the good and disposition to act for the good. What can we learn from Washington at Valley Forge? What do Helen Keller and Annie Sullivan teach us? Why did Gandhi march to the sea? The Core Virtues program seeks to inspire children to act justly, live generously, and pursue their life path with courage, prudence, and hope. In that moral journey good stories are the spur, and activities for habit-formation should be age-appropriate. Between Kindergarten and grade 6 children can be encouraged to exercise respect by treating their classmates and teachers well, show diligence by doing their homework carefully and on time, stewardship by caring for their desks, rooms and school, generosity by serving the elderly or the needy, courage by being willing to act in a play, love of country by learning the nation’s poetry or songs, compassion by helping a child on the playground in need, humility by willingness to be last in line, and hope by not assuming the worst outcome of events. These are appropriate elementary school goals. But no elementary school time should be spent on tendentious culture war conflicts and activities. If a topic is currently being disputed in the political and social arena, leave it there. Good stewardship of the young requires that elementary school teachers and leaders respectfully consign those topics to adults with fully developed pre-frontal cortices and some mechanisms of emotional self-control to debate and ultimately settle. In other words: when a teacher presents a unit on antebellum America and concludes that America’s history of race-based slavery has made it “systemically racist” today, he oversteps his bounds. He is in the realm of opinion and theory. When legislators mandate that public school third graders see a charming animated movie on fetal development, they too overreach because they risk antagonizing half their parent community. When a teacher encourages students to choose their pronouns, she goes too far: the “non-binary” nature of sex has not been empirically established, nor have the medical consequences of school social affirmation. When Social Studies teachers urge students to march for gun ownership rights or for the elimination of them or for the closing of fossil fuel plants, they move from the realm of shared understanding to partisan policy advocacy. Those who urge these activities and conclusions at the K-6 level are disrespectful of the ongoing debate and are acting irresponsibly as stewards of minors. Contemporary defenders of the above initiatives may see themselves as “virtuous:” defending justice, extending compassion, advancing liberty, or protecting the environment. But they are advancing an agenda. Agendas belong in the adult political arena: they do not belong in K-6. Elementary schools need to remain respectful, responsible, and above all - elementary. Mary Beth Klee This is an updated version of an article we ran in May 2019. Research at Princeton University on the neuroscience of storytelling inspires new enthusiasm for the soundness of character education that relies on "telling our stories." Dr. Hasson's latest research finds similar neural synchrony (described below) for adults and children involved in one-on-one, face-to-face play. Such synchrony facilitates development of the prefrontal cortex, which is key to learning, planning, and executive functioning. Did you know there is a “neuroscience of stories”? Experts in the fields of psychology and neurology are looking at what happens to the human brain when we are told a story. How does the brain react to this form of verbal communication, particularly when stories are told to a group? The results affirm something Core Virtues teachers have long intuited: the telling of stories creates a bond, and puts the student audience “on the same wavelength.” That facilitates communication and promotes harmonious interaction in the classroom. “It gives us a common language,” one teacher told me. We are now learning that this sense of “being on the same wavelength” when you listen to a good story, is literally true. Research scientists at Princeton University, led by Professor Uri Hasson, want to understand when our “cortical activity” is idiosyncratic (unique to individuals or to subgroups) and when are our responses are shared. Are there times when brain activity synchronizes, facilitating communication? Or is human brain activity largely idiosyncratic? At Professor Hasson’s lab, they’ve been investigating this for years, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and intracranial EEG (iEEG) recording to chart brain activity.  Not surprisingly, patterns of human brain activity are idiosyncratic in various situations, even when individuals are gathered as a group and even when they are listening to the same lecture. But when people in a group are told a story (such as one from “The Moth” radio hour) the group exhibits synchronized brain activity. For the time of the story, “brain coupling” takes place. Patterns of brain activity from the speaker are echoed or repeated in the minds of the listening audience, and the audience, composed of any number of individuals, aligns to the same wavelength. Measured brain responses show the activation of the same regions in the same way. This is known as "neural synchrony" and that synchronization dramatically facilitates human communication. Hasson’s lab conducted all sorts of experiments to determine whether such brain wave alignment had to do with sound of voice, sense of words, or a specific language. But when a given story was translated into Russian for another group of native speakers, the scientists got the same results: brain wave patterns that were both synchronized from speaker to audience, and nearly identical to patterns generated by the English speaker. (You can watch Dr. Hasson explain this in his TED talk at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FDhlOovaGrI) What does this sophisticated research have to do with character education, the Core Virtues Morning Gathering, and ultimately, creating a more civil and fruitful society? A lot. Go back to April with its focus on forgiveness. Imagine (or recall) the second grade teacher at Morning Gathering who begins to read Robert Coles’s The Story of Ruby Bridges to her fidgeting class. We all know that within seconds, the fidgeting dies down, and twenty little minds and hearts are tuned in to the story of the brave six-year-old girl in Louisiana, who, because of her skin color, was unwanted as a student in an all-white public school. The first African-American child to integrate the school in 1960, Ruby Bridges had to be escorted (for her own protection) by federal marshals while a crowd jeered, booed, spat and threw things. Once inside she prayed God would “forgive these people. Because even if they say those bad things, they don’t know what they are doing.” That took courage. That took largeness of heart. Every child in the room hangs on each word, identifying with the young protagonist. They are on the same wavelength. From then on, when the teacher points to the wisdom of forgiving classmates who may have called them names or unintentionally hurt them on the playground, they have a common frame of reference. Now when they talk about the need to respect classmates regardless of their skin color or clothes or the place they were born, the class has a common role model, and a shared commitment to higher goals based on a real-life story that moved minds and hearts in the same direction when they were all together.  See our review of this timely 2-6 book in May. See our review of this timely 2-6 book in May. The beauty of the Core Virtues approach to character education is that by regularly employing a treasure trove of stories (from history and literature) to exemplify the virtues, we build the common ground so essential to communication and fruitful interaction. We bring children’s hearts and minds together for a good goal, for human excellence. That’s what the virtues are: human excellences. The stories of respect, responsibility, diligence, generosity, courage, compassion, humility, hope, and more, move kids' hearts, and now we know, unite them in a profound way. For fifteen minutes three times a week, “brain coupling.” "Neural synchrony." Who knew? How wonder-ful. And as we think about divisions among us and our quest for a more civil future, that's also a source of hope and joy. Mary Beth Klee For the study referenced above on adult-baby sync up during one-on-one play and story time, see https://www.princeton.edu/news/2020/01/09/baby-and-adult-brains-sync-during-play-finds-princeton-baby-lab. “The Morning Check-In is the heart of the day.” When I read those words recently on a Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) website, I did a double-take. Since 1992, the Core Virtues program has proudly proclaimed “The Morning Gathering is the heart of the day.” It’s all over our website. By “Morning Gathering” we refer to a K-6 circle time meeting that celebrates a given virtue with a great story. In April, for example, the teacher reads an inspiring picture book like Me and Momma and Big John that shows an artisan (and her son) learning humility by seeing her work as part of something larger and more meaningful than personal statement.  Morning Gatherings are times for kids to leave behind whatever happened at home last night or at drop-off that morning, and to be drawn instead into a well-written story with intriguing characters who model courage, compassion, respect, or diligence. This is the “fill ‘er up!” time of the day. For fifteen minutes they are in a story where life is hard, but characters exercise moral excellence and find a way. Children are given hope. Then they turn to phonics or math inspired to do their best and be their best.  So, what are “Morning Check-Ins”? What’s the difference? It’s huge. The Morning Check-In in SEL programs generally involves taking the emotional temperature of the class -- individually. Teachers invite students to begin the day by reflecting on how they are feeling. Frequently used posters feature at least sixteen facial emojis that invite children to reflect on whether they are happy, content, focused, and calm, or twelve other choices such as sad/upset, tired, bored, sick, silly, worried, frustrated, excited, mad/angry, need some space, yelling, or out of control. Teachers employ these posters in different ways, but enthusiastically note in their reviews: “I use their choices to guide our morning meetings.” In other words, take time to reflect on what’s troubling or exciting them - and there are lots of possibilities. “I like to use this in the morning and after recess to see how my students are feeling,” one teacher writes. In other words: ask them to focus on their feelings at least twice a day.  What’s wrong with this picture? Abigail Shrier can tell you. The Wall Street Journal investigative reporter’s new book, Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up, has a lot to say about our current counter-productive tendency to focus on emotions. It is “airborne” in our culture and in our parenting, and is being encouraged in schools across the country. And it's debilitating. Starting from the statistically proven observation that “we have raised the loneliest, most anxious, depressed, pessimistic, helpless, and fearful generation on record,” Shrier asks “why?” She documents a widespread “culture of therapy” in modern America, which emanated originally from the mental health community. In the past two decades it has infiltrated schools and is causing “iatrogenic” harm - unintentional harm caused by the healer. Shrier asserts that in education many of these therapeutic practices (which she describes as "social and emotional meddling") are eating into childhood resilience. They induce an unhealthy focus on the least reliable of our moral and mental health indicators: emotions. As one who has watched SEL programs bloom and proliferate over the years, I know that most SEL practitioners are well intended, and SEL schools promote goals that appear to echo aspects of virtues-based character education. Their stated goals — promoting safe and caring classroom environments, helping students develop “self-management,” navigate social situations, make responsible decisions, and cultivate “empathy” and “community participation” – sound very much like Core Virtues’ focus on respect and responsibility in schools, diligence and self-control, compassion for others and community service. The verbiage in SEL programs at times overlaps with verbiage in virtues-based education. But the pedagogy is worlds apart and the results are too. SEL programs turn the student inward. Their standards and competencies include self-determination, self-regulation, self-management, self-care, self-awareness, and self-talk. They attempt to balance these against social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. Through an elaborate schema intended to integrate all aspects of school life, they convey to the student: Mindfully consider your own state of being and emotions in the present moment.  Initially developed to improve the academic performance of troubled inner-city youth, SEL programs have morphed. They currently promote a lot of counter-productive interior analysis and rumination. What is rumination? It is the tendency to mentally review and constantly rehash past injuries and the ways in which things have gone or could go wrong in a given situation, to focus on possible obstacles impeding forward movement. Shrier has gleaned insights from many psychiatrists and psychologists. She points out that by constantly asking children to focus on their feelings, one is very likely to reinforce negative emotions in children afflicted by them. And not just that - we are likely to introduce negative emotions to children who hadn’t considered them. Let’s see: am I a little off today? Yes, I guess I should focus on that. This “emotional state” orientation instead of “action” orientation impedes growth and maturity. By asking kids to focus on their feelings, we often cripple them. “Academic psychologists note that people who adopt an ‘action orientation’ are able to focus on a task without getting distracted by thoughts about their current emotional or physical state,” Shrier writes. “Those who adopt a ‘state orientation’ on the other hand, are thinking more about themselves in the moment: how prepared they feel, that crick blossoming in their neck, the email they haven’t answered. Unsurprisingly, an action orientation makes it much more likely that you actually accomplish the task.” Michael Linden, MD, expert on mood disorders and professor of Psychiatry in Berlin, notes: “State orientation keeps you from being successful in anything.” Psychiatrists who treat patients crippled by emotional disorders often advise thinking LESS about one’s emotions. Shrier reminds us, “No winning head coach asks his players to dwell on their feelings at halftime. Instead of constantly asking kids to name how they feel in the moment, adults should be telling kids how imperfect and unreliable their emotions can be … that they sometimes deserve to be ignored. Healthy emotional life involves a certain amount of repression,” she writes in a recent Wall Street Journal (March 8) editorial. Abigail Shrier is not going to make a lot of friends by suggesting the importance of repression, but we all know that she is right. The times in our lives when we have accomplished the most meaningful goals are probably those in which we were somewhat anxious and stressed, but denied the emotion of fear’s power over us, exercising courage. Courage, the Core Virtues program defines as “moving beyond fear to venture and persevere.” Venturing and persevering is key. Why is Morning Gathering the heart of the day in Core Virtues programs? Because it provides imaginative fuel for noble action. It inspires hope. On a regular basis children are encouraged to look not in and down, but up and out. Treated to stories of boys and girls, men and women, sometimes dogs, cats, bunnies, mice, and hedgehogs, encountering difficult situations, kids identify with attractive characters who move beyond fear or crippling love of self to act heroically. They encounter great models. Plato reminded us that the purpose of stories is to help students fall in love with virtue, the excellences required of mature and fruitful adults. So, let’s help the kids grow up. Leave rumination behind; make sure these literature-based Morning Gatherings provide all-important moments of hope and inspiration. Mary Beth Klee  A pioneering female student arrives at the University of Notre Dame in the 1970s. A pioneering female student arrives at the University of Notre Dame in the 1970s. In March, Women’s History Month, we’re paying special attention to the challenges that young girls face growing into adult womanhood. Bravo to all the mothers and daughters building strong relationships! This is an updated version of our 2023 article, highlighting new research. Since 1987 our nation has celebrated “Women’s History Month.” That decision (a Congressional resolution) came on the heels of a 1970s feminist revolution aimed at opening for women any career path they chose and any future they deemed worthy. The women’s movement of that era sought educational and professional opportunities equal to those offered men, and not restricted to motherhood and home-making. Young women who came of age in the 1970s largely lived out those dreams and forged paths that would open doors for the next generation of women. In 1970, men outnumbered women at the university by 58 percent to 42%, but by 1980 the enrollment by sex was 50-50. Now women surpass men as a percentage. And career paths were unlimited: women became architects, astronomers, bankers, engineers, entrepreneurs, fighter pilots, etc. The Core Virtues "Women’s History Month" tab recommends numerous wonderful children’s biographies of the many trailblazers in those fields. And most of the women profiled, from Abigail Adams to Eleanor Roosevelt, were also proud to be wives, mothers, and homemakers. It would seem that with all this progress, there has never been a better time to be a woman. But evidence from many sources suggests the opposite. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) released data showing that teen girls are “engulfed in [a wave of] violence and trauma.” And we see that reflected in news stories. Online bullying incidents among girls have become toxic and tragic. In 2022 fourteen-year-old Adriana Kuch was savagely attacked by other teen girls in a New Jersey high school hallway. Bystander girls filmed the beating, then posted it on Tik Tok, with ongoing taunts about how she “deserved it.” Humiliated, ninety-eight pound, five-foot-two Adriana, who loved animals and worked with special needs kids, committed suicide two days later. This is an extreme case with devastating consequences – but it is not isolated. Teen girls “beating up” on other teen girls via social media is now a national epidemic. For decades girls have been infamous for cliques that exclude those who are “not cool,” (satirized in the 2004 movie Mean Girls) but since 2007 “mean girls” have been armed with a new weapon: the smartphone. Amid screen-addicted friends, they spread shame, mockery, and self-doubt. No wonder the CDC finds that 57% of teen girls report themselves “persistently sad or hopeless,” and that 30% have considered suicide. Here's another alarming stat for the future of womanhood. One in five thirteen to seventeen year-olds are identifying as “transgender,” and the vast majority are pre-teen and teen girls who showed no sign of gender dysphoria (discomfort in the sex of their birth) in early childhood. What was once a rare psychiatric condition (until 2013 known as “gender identity disorder”) that manifested itself almost exclusively among pre-school boys who identified as girls--has become a social trend.  Girls as young as fifth grade are opting out of growing into adult womanhood. They cut their hair, change their name and pronouns, adopt male clothing, bind their breasts, and contemplate puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and perhaps the eventual top surgery and phalloplasty. Child psychiatrist Miriam Grossman, who specializes in gender dysphoria, warns of the harm young women may inflict on themselves as they abandon nature. She speaks out forcefully in her new block buster book, Lost in Trans Nation. Aided by an errant medical community, girls are being taught that if they are uncomfortable with their changing bodies (who wasn't?), maybe they are not really girls... Maybe they're trapped in the wrong body; they may be male ... or non-binary ... or somewhere else on the spectrum. Why not insist on puberty blockers while they make their "informed decision" about gender? Why not ignore the dimorphic nature of sex, leap-frog the natural process, and preserve alternative gender options? Dr. Grossman can tell you why not. These current trends bode ill for the future of womanhood. Girl-on-girl physical, emotional, and verbal abuse of the scale we are now seeing is new and frightening. It mirrors the behavior of fictional pre-teen boys in William Golding’s 1954 novel Lord of the Flies, in which cruelty, tribalism, and savagery come to characterize British boys stranded on a desert island. Typically, we did not associate this behavior with girls. Why are these behaviors developing among our girls? There are three answers: one psychological, one technological and the other cultural. Psychology first. Teens are a peer-driven group. This is the age at which young people seek to establish independence from parents, and strengthen their own identity and self-worth, often in tightly knit and trusted peer groups. Teen girls are particularly insatiable in their desire for peer group connection. When those peer groups are healthy (kids who are excited about learning, the arts, outdoor activities, sports, faith, or supportive of helping others) the experience is positive and a step in emotional maturity. When peer groups are power- and exclusion-driven (kids who see coolness in wealth, appearance, clothing, manner of speech, substance-use etc.) the experience can quickly become toxic. Such peer groups thrive on ostracism and the rising incidence of bullying in American middle and high schools attests to that. Throw into this mix our new twenty-first century companion: the smartphone, born as the “iPhone” in 2007. America’s parents have been reeling ever since. According to the Pew Research Center 88% of American teens own a smartphone (the average age of the adolescent user is 12-13), and as of 2019, 95% had access to one at home. 78% of teens check their phones at least every hour. 72% feel the urge to respond to their texts of phone notifications. 59% of parents think their teens have a smartphone addiction. On the surface, this tool of technology is morally neutral; it has the potential to connect, inform, and entertain us all. But the advent of social media has enabled online peer groups. We are seeing teen cyber-bullying, and in-group out-group exclusions on an unprecedented scale. Tik-tok, Snapchat, and many other apps have come vehicles for sharing mortifying photos, publishing cruel comments, and encouraging self-doubt and self-hatred particularly among young girls. Many teen girls live in fear of what will be said about them online--a forum they do not control. Other girls use social media to seek out a peer group that gives them both a unique identity and a support group. Count most of the newly trans teens among the latter. Vulnerable or just plain curious young girls find plenty of support online for ditching society’s and their parents’ expectations of them at the most basic level – their sex. Puberty for girls has always been challenging, involving physical pain and discomfort, emotional rollercoasters of mood swings, and a large dose of insecurity. And since the 1970s, we’ve been broadcasting loud and clear that on the other side of the puberty divide, men have the upper hand. Women have to be twice as good to compete. And women have the added “burden” of childbearing and home making. So, what could be more appealing than opting out of all that? Abigail Shrier’s 2020 book Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters documents the near-universal phenomenon of these young girls’ deep involvement on social media forums that offer new and exciting peer groups. Trans peer groups advertise themselves as a new family, and even encourage teen distancing from their biological families, as they establish their new gender non-conforming identity. Again, often with tragic results. A recent case in Virginia led one fifteen-year-old girl to leave her family home and meet up with her “online family,” only to discover that she fled to the arms of human traffickers. Why are girls doing this? Because in the realm of culture we have an unfinished feminist revolution. The Core Virtues program highlights compassion, faithfulness, and mercy as March virtues. These are virtues for both sexes, but they have historically been most closely associated with women. The nineteenth century German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously held up the “eternal feminine” (ewig-weibliche) as the highest human ideal. “The eternal feminine draws us on high” were the words with which he closed his masterpiece Faust. That feminine ideal embodied such traits as beauty, truth, love, compassion, mercy and grace. It was embraced by American feminists Margaret Fuller and Edna Cheney. It’s no accident that our March Core Virtues “heroes” have been mostly “heroines” – Clara Barton, Anne Sullivan, Mother Teresa. Compassion, mercy, and grace are the qualities that have characterized not just significant social reformers, but also the familial pillars of our society -- good mothers. The 1970s feminist revolution broadcast the message: motherhood and homemaking is not the whole story. But often the subtext was: motherhood and homemaking are for those who can’t cut it in the “real” world of commerce, enterprise, or academia. Motherhood is a biological accident of nature, not a worthy aspiration. And please don’t tell me to be meek and mild. The message we have not sent our daughters in the last fifty years is: It’s great to be a girl. Girls are not only as smart as boys: you have special gifts of empathy and human connection. The most special is that you, and you alone, get to be a mother. What we girls rightly call our “private parts” makes it possible for you to bear a child, nature’s greatest gift and mystery. We live in amazing “both-and” times. In our times, you get to be both a mother and a doctor – or a nurse. A mother and a social worker or a soldier. A mother and an astronaut or administrative assistant. A mother and a historian or homemaker. A mother and a librarian or a lawyer. And so on. You don’t have to be a mother. Many women are happy in other life paths, and you can use your empathy, compassion, and many gifts in other ways – like Clara Barton or Jane Addams or Emily Dickinson. But you can be sure too, that if you’re in any of those marketplace professions named above, you’ll use every one of those talents as a mother. And you can’t beat motherhood as a path to virtue. You have an unparalleled opportunity to grow in love, fortitude, compassion, faithfulness, and mercy: all the qualities that those girls who are descending into bullying, physical violence, and internet savagery so obviously lack. I am taking a suggestion from the closing chapter of Abigail Shrier's book and asking that our March message to young women be: it’s great to be a girl. I’m proud to be she. -Mary Beth Klee To read more from Telling Our Stories, visit our Blog Archives page. Gallup polling tells us that in 2013, 85% of young voters (ages 18-29) said they were "extremely" or "very" proud to be an American. A decade later that number stands at 18%. This plummeting figure should concern us all because devotion to country spurs citizen commitment to progress and contributes to a healthy sense of belonging. Detachment and cynicism yield only "meh." And we don't need that. We repost our slightly revised 2023 blog on Love of Country.  In his 2017 article, “A Sense of Belonging” E.D. Hirsch Jr. drew attention to young people’s declining sense of attachment to their country and asserted that has contributed to racial and ethnic polarization and “hyper individualism.” (“Out of one, many.”) Hirsch attributed the decline in large part to the failure of schools in the past six decades to teach substantive content (U.S. history, civics, biographies, poetry, songs) and to emphasize instead the primacy of the individual and his/her individual interests. Teach the child, not the subject has been the mantra. Lost in the process has been an understanding of our shared past, a sense of community, belonging, and solidarity with our fellow citizens. Much diminished is the devotion to country that spurs students to contribute to the advancement of something larger than themselves of which they are a part. Hirsch called for cultivation of “the right kind of nationalism” in American schools, one that educates about our past, our heroes and milestones, one that enshrines our highest ideals. “The right kind of nationalism is a very good thing,” he asserted. The right kind of modern nationalism is communal, intent on including everyone. The wrong, exclusivist kind, exemplified by the racism of the Nazis, gave all nationalism a bad name and helped turn the post-Vietnam left away from nationalism of any sort. The sentiment was that most countries are pretty bad, especially big ones that prey on little ones. When designing the K-8 Core Knowledge Sequence and in revising it since, framers abandoned the insular social studies framework of “me, my family, my neighborhood, my community” that had characterized elementary education since the 1970s. They substituted strong U.S. and World History programs. Children were encouraged to see themselves as part of the long arc of human history (beginning with the Ice Age, moving through ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, Greece, Rome, the Middle Ages worldwide, and modern times). And through their studies in U.S. history from first to eighth grade, students have been encouraged to see themselves as part of the American journey, which has been a worthy and unique one. Let’s go ahead and say it: an exceptional one.  The American Revolution with its trailblazing insistence that “all men are created equal” was not an immediately realized ideal. But the establishment of a republic on that principle, the principle of freedom and equality, was a radical departure from the norms of the times, when monarchy, oligarchy, and tyranny prevailed around the globe. At the time of the American Revolution, when those words were proclaimed, the vast majority of the world’s people lived in some sort of “unfreedom” as serfs, slaves, or indentured servants. (The American population itself was 20% enslaved.) 1776 was a root-level departure. And the entire American story has been one of living out the ever-expanding meaning of those words to include women, Native Americans, people of color, people of all races and faiths. When U.S. history is told fully and honestly, we see injustice in our past – as we do in world history. But from a historical standpoint, no nation has provided more opportunity to more people of more varied backgrounds than the United States. We do our children a disservice when we fail to tell these stories. Stories of key people and key moments in time, along with stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary things. We should tell the stories of George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Abe Lincoln, and also Benjamin Banneker, Abigail Adams, Sacajawea, Clara Barton, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sojourner Truth, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass. Surely, let's focus on Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, John Muir, Dwight Eisenhower, but also George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells, Eleanor Roosevelt, Frances Perkins, Rachel Carson, and Cesar Chavez. Children can and should be proud of them all. These are the stories that instill hope and cultivate a shared love of our country and its ideals. Many, many of those are featured in our February “Virtue of the Month” tab, in our Presidents' Day tab, and on our Black History link, our Women’s History link, our Immigrant Heritage link. Many are immortalized in the Childhood of Famous Americans series, and many re-envisioned in the Tales of Young Americans series we spotlight in our February overview. In his Farewell Address, George Washington addressed a country scarred by deep divisions. He wrote: "Citizens, by birth or choice, of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations." In his final State of the Union address in 2016 Barack Obama picked up that theme. He called on Americans to listen to “voices that help us see ourselves not, first and foremost as black or white or Asian or Latino, not as gay or straight, immigrant or native born, not as Democrat or Republican, but as Americans first, bound by a common creed. Voices Dr. King believed would have the final word – voices of unarmed truth and unconditional love.” Improvising on Walt Whitman's I Hear America Singing, he reminded us: "And they’re out there, those voices….they’re busy doing the work this country needs doing...  I see it in the worker on the assembly line who clocked extra shifts to keep his company open, and the boss who pays him higher wages instead of laying him off. I see it in the Dreamer who stays up late to finish her science project, and the teacher who comes in early because he knows she might someday cure a disease. I see it the American who served his time, and made mistakes as a child but is now dreaming of starting over – and I see it in the business owner who gives him that second chance. I see it in the protester determined to prove that justice matters – and the young cop walking the beat, treating everybody with respect, doing the brave quiet work of keeping us safe … That’s the America I know. That’s the country we love. Clear-eyed. Big-hearted….Optimistic that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word. That’s what makes me so hopeful about our future. Thank you, God bless you. God bless the United States of America.” Mary Beth Klee Dr. Klee holds a Ph.D. in the History of American Civilization from Brandeis University.

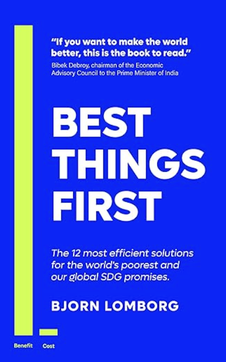

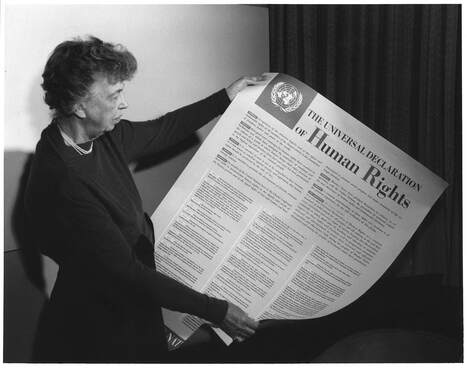

Janus, for whom the month of January is named, is the Roman god who has one face staring backward and another peering forward. He is a great metaphor for this month, having ended one chapter even as we open another. Some images of Janus show the backward-looking visage as bearded and horned, while forward-facing Janus is clean-shaven and smooth cheeked. Backward-facing Janus scowls at the weight of the past. Forward-looking Janus smiles: he’s a youth with the added wisdom of experience literally behind him. He’s ready to GO FORTH ON GOOD PATHS. My candidate for the Janus Award this January, a just-now designed award for intellectual courage and common sense, is Bjorn Lomborg. The Danish economist looks the part. He is smooth-cheeked and perennially boyish, though next year he will turn 60 (with wisdom of the past behind him). Throughout his career, he has specialized in clear-eyed and unexpected thinking, championing workable solutions to thorny issues with buoyant enthusiasm. But Lomborg’s most recent book, Best Things First, is arguably his finest. In it he proposes the twelve most efficient solutions for aiding the world’s poorest, and for fulfilling the UN’s very ambitious sustainable development goals (SDG). A little background: in 2012 (pre-pandemic Eden and buoyed by progress made in meeting eight UN Millennium Development Goals) UN teams took up a new task: deciding goals to be met by 2030. These were dubbed “Sustainable Development Goals.” Rather than replicate the successful Millennium model of specific targeted goals, world leaders came up with seventeen major rubrics and 169 total goals that promised numerous wonders by 2030: the eradication of poverty, hunger, and disease. An end to war, a halt to climate change. The advance of education and the abundance of clean water. Gender equality. The extirpation of corruption and the end of food waste. And many more. Organizational psychologists insist that if you have more than three priorities, you have none—so this was problematic. Then came the pandemic—which affected all of us, but devastated those most in need. African nations fell further behind than ever before.  In his most recent book Bjorn Lomborg looks back at how we got here, and then reflects on the fact that we are not even close to meeting the new Sustainable Development Goals. But we could get much closer much faster and for a very reasonable amount of money, he argues. “Our goal is to pinpoint where we can create the most value for humanity per dollar, rupee, or shilling spent.” Where is the biggest bang for our buck? Lomborg leads off with a clear-eyed observation: “We all want a better world. Unfortunately, our efforts are often hampered by wanting to achieve not just some but all good things, at once, many of which are nearly impossible, prohibitively expensive, or terribly inefficient, or all these things at once. So this book outlines how to do the best things first.” His twelve “best things” solutions (each a chapter) target tuberculosis, maternal and newborn health, malaria, nutrition, chronic disease, childhood immunization, education, agricultural R&D, e-procurement, land tenure security, trade and skilled migration. In twelve peer-reviewed, data-rich studies he concludes that if the world spent $35 billion dollars yearly —which is about the amount that we spend on cosmetics—we could dramatically improve the lives of the world’s poorest. Compare this with “it takes trillions” annually to solve climate change. (John Kerry)  Bjørn Lomborg Bjørn Lomborg Lomborg estimates that for that amount “we can save 4.2 million lives annually, and we can make the poorer half of the world more than a trillion dollars better off each and every year. We can almost entirely end tuberculosis, which needlessly kills more than a million people each year. We can reduce the death toll of chronic diseases by 1.5 million… We can increase yields in agriculture, making farmers produce more, consumers pay less, while avoiding hunger for more than a hundred million people. And we can ensure almost every kid in the poorer half of the world actually learns while they’re in school, thus raising these children’s eventual incomes collectively by more than $600 billion per year. In short we can achieve a vast amount while spending relatively little.” While chock full of data, the book is very readable. Lomborg intends it for policy makers and philanthropists and for all people of good will who are looking for concrete ways to make a difference. “Please pick one of these twelve areas for your coming investments,” Lomborg urges. Those investments can be investments of time and attention too – particularly as we ask students to think about creating a better world. It’s not all about recycling. It takes intellectual courage to promote solutions that are at once simple and effective, but outside the mainstream view of immediate imperatives. It would be easier to champion trillions for climate change. Still, Lomborg is making inroads. We can’t do everything at once, he cautions the UN. Let’s do the best things first. The endorsement of his work is coming from sources as diverse as Bill Gates, Larry Summers, Jordan Peterson, Terrence Keeley, and international development officers worldwide. Now, if we could just start charging forward on these good paths… That’ll take courage. Mary Beth Klee "If we do not lay ourselves out in the service of mankind, whom should we serve?” Abigail Adams (September 29, 1778) This December, as the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights turns 75, we do well to reflect not just on the document, but on the woman whose service to humanity made the work possible. Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady and widow of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, chaired the drafting committee for the landmark document. After two years of work, she secured consensus for this pathbreaking text among a committee that included Western philosophers and Confucian advocates. She mustered unopposed adoption of the document by the General Assembly of 58 nations. This was a gargantuan task, undertaken with perseverance, finesse, a spirit of service and yes, hospitality. But let’s look back. As a shy and insecure child who lost both parents by age 10, curious, idealistic Eleanor Roosevelt developed a heart for others. Her involvement with social causes predated her marriage to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and contributed to her unique and active embrace of the role of First Lady. From the time FDR was elected in 1932 promising a “New Deal” for suffering Americans, Eleanor traveled the United States, learning firsthand about the plight of the most afflicted. Whether miners, World War I veterans, laborers, African-Americans, impoverished children, or the disabled, First Lady Eleanor gave voice to their needs. She did this by regularly informing her husband, but also through her daily “My Day” newspaper column, her weekly CBS radio show, her monthly "If You Ask Me" magazine column in the Ladies Home Journal, and her regularly scheduled press conferences -- open only to women reporters. (Eleanor had observed that without that stricture, news outlets sent only men).  In 1936, the First Lady’s hospitality was extended to the stunning contralto Marian Anderson, who was asked to perform at the White House. She was African-American and that raised eyebrows. Three years later, when the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow Anderson to perform at their 4000-seat Constitution Hall venue, Eleanor resigned from the organization. She arranged for the artist to perform at the Lincoln Memorial in a landmark concert that moved hearts and lifted spirits on the eve of war. Seventy-five thousand (not four thousand) were in the audience. (Video of the concert here.) During World War II Eleanor wanted to serve troops suffering the hardships of war. She went to the frontlines in the Pacific theater, visiting hospitals and soldiers in Guadalcanal, holding plasma for doctors doing triage, walking more than fifty miles of corridors in a single day, and carrying in her pocket a prayer that said “Lord, lest I continue in my complacent ways, help me to remember that somewhere someone died for me today.” When Franklin died in 1945, Eleanor mourned and wondered what momentum her efforts might have without him. But she did not think her service to her country should die with him. After a brief withdrawal from politics, Eleanor returned to the public sphere, traveling the country and speaking out on public affairs. Harry Truman, who succeeded FDR, found Eleanor annoyingly critical of his implementation of the New Deal. Mrs. Roosevelt was beloved, listened to, and consistently audible/visible. She had persuasive powers.  Hmmm.... Why not ask Mrs. Roosevelt to head the US delegation to the new United Nations? Rumor had it that they were struggling to draft a universal declaration of human rights, an almost impossible task given the roster of nations, which included the Soviet bloc, apartheid South Africa, and restrictive Saudi Arabia. The meetings for that work would be largely in Europe, moving Eleanor overseas. To Truman’s great delight and to the chagrin of the entirely male US delegation, Eleanor accepted. Her work in the next two years as Chair of the drafting committee for a new Universal Declaration of Human Rights was arguably Eleanor's greatest contribution to public life. She was gifted not simply in devotion to principle and ideals, but in understanding the thoughts and needs of others. Fluent in five languages, she knew the importance of making others (especially one’s guests) feel at home. She treated her collaborators on this project as her guests, and they often were. Eleanor believed in conversation. Dinner parties, informal meetings, and one-on-one conversations were her forte. Biographer Allida Black notes that in the last sixty days before the hard-fought document went to a vote before the General Assembly, Mrs. Roosevelt held (and attended) 85 working sessions in sixty days, and more than a hundred individual meetings with members of the General Assembly or their staff on top of those 85. Though several nations abstained, the document was approved without opposition by the General Assembly on December 10, 1948. On the heels of atrocities recently experienced in World War II and unfortunately ever-present in our world-- the preamble proclaimed: “Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind,” this declaration of shared principle was necessary. Article 1 featured pathbreaking language. “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Who had rights? ALL human beings – men, women, children. And a right to what?

All hail to Eleanor Roosevelt, a woman of hospitality and tireless service to humanity; and all hail to the vision enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Both provide a beacon of light in the darkness of our December nights. - Mary Beth Klee When I was little, my family’s Thanksgiving tradition was going to national parks. It may have been a little unorthodox, but ended up being very fitting: we were certainly prompted to gratitude for the beautiful surroundings, and we were also prompted to gratitude by the lavish hotel Thanksgiving dinners we enjoyed without any prep or cleanup. On one of those trips, when I was about thirteen, we went to Zion National Park. Zion is in Utah, full of stunning cliffs and named by Mormons who must have thought that the staggering cliffs and vistas reminded them of the Promised Land. Everywhere you look in Zion, especially in the fall when we traveled there, you are met with overwhelming natural beauty, as the leaves change color and the red rocks tower out of deep valleys. I remember even at that age dreaming of living in one of the tiny cabins we saw along the winding road into the park, making a home in a peaceful, undisturbed environment kept pristine from the developed world outside. Costco is not exactly a peaceful, undisturbed environment. Another haunt of my childhood days, it shares with Zion National Park at least the sense of soaring space—in this case a warehouse space, where you can buy everything from plush hoodies to $20 handles of vodka. When I was young I loved going with my mom and trying all the samples, set up like stops on the Candy Land board as you wind your way through the concrete aisles. The shelves at Costco tower over you, overwhelming and yet inviting like the crags at Zion National Park.  Image #2 credit: ZidaneHartono (CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED) Image #2 credit: ZidaneHartono (CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED) The sense one has upon entering Costco is one of abundance. There is a food court where you can get a huge hot dog and a drink for $1.50, and a slice of pizza the size of your face for $2. There are cases of 2 dozen eggs or 36 cans of Diet Pepsi. And that’s just the food—you can usually find a large tent at Costco, lots of clothes (predominantly outerwear and sweaters, at this time of year), couches, flat screen TVs. Filling my cart with every material need I have, or even just wandering around Costco knowing I could do so, awakens certain feelings that I also had in Zion National Park when I was 13. At the time, hungry for beautiful places and beautiful feelings and never hungry for food, my experience at these beautiful national parks was of great abundance—great “scope for imagination,” as Anne of Green Gables would have put it. 13-year-old me would have found less scope for imagination at Costco than I have now, but I’ve grown since then. The self in my twenties can see affordances that 13-year-old me couldn’t see in this apparently sterile warehouse space—instead of seeing cliffs where fantasy armies or herds of unicorns could gather, I see a bottle of wine that could furnish a dinner party, a blanket that could keep a baby warm, a couch that could be the focal point of a future living room. I feel surrounded by possibility at Costco just as I used to feel—and still feel—surrounded by possibility in nature. But my world has expanded, and places that used to be uninteresting have— with the addition of more experiences and, frankly, more needs—become interesting. Money is more interesting when you’re trying to build a life with it. Houses are more significant when you imagine potential lives in them. People are more interesting when you remember to ask them questions, which I don’t always do. When I was young I used to promise myself I’d never forget my shimmering visions, the imaginary worlds that I could see outside the window of my fourth-grade classroom, the secret code that decorated my middle school notes and my high school SAT test booklet, the dramas and stories that used to carry me, almost levitating above the ground, through the banality of everyday life. And I haven’t forgotten. But I have made some discoveries. The enchantment that wrapped my imaginary world as a child has slowly expanded to encompass even places like Costco, or the car wash, or the long freeway crossing Indiana into Michigan. The enchantment is there, when I tap back into it—vividly apparent in the setting sun on golden November days, in the wind whisking leaves past my window, but also when I go to Target or meet a friend for coffee or see a bird in the airport. I won’t exaggerate—a lot of the time I let these things pass me by. 13-year-old me was vividly, intensely sensitive to every passing impression, looking out the window and scribbling down musings, imagining dramatic scenarios. Some of that energy and sensitivity go in unproductive directions now that I’m an occasionally stressed, often anxiety-ridden adult. Sometimes it’s easier not to look too closely, not to let my imagination run away—because it doesn’t always run away into beautiful places now. But on my best days, it all seems significant, even the errands to pick up 36 rolls of toilet paper. The mystical physicality of Zion National Park has transmuted itself into the soaring shelves at Costco, and the dramas I used to spin in my mind now meet me in the faces of the people who hand out samples and people I sit down with at dinner and people who call me while I drive. Now I see the beauty of the things themselves, and see that the drama was really inside them the whole time: inside the way that leaves drop at the beginning of winter, inside the human stories that are constantly unfolding around me. Reality is no longer a mere backdrop—reality is where I see the transcendent things that I always imagined, not only shining through, but shining within. Guest columnist Emily Lehman is Artistic Director at Core Virtues and has a monthly Substack newsletter, Dubious Analogies. This post is modified from its original form at dubiousanalogies.substack.com. In October, as the “back to school blush” is off the rose, children in Core Virtues schools focus on the virtues of diligence, perseverance, patience, and self-control. They are being asked to stretch and push themselves “despite difficulty and hardship.” “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” With those words in September 1962, John F. Kennedy summoned American commitment not just to space exploration but to a nearly unimaginable goal – a manned spaceship on the moon before 1970. The task of a lunar landing and safe return of astronauts to Earth was incalculably complex, and the US was playing catch-up ball to the Soviets. JFK announced, “we will not founder in the backwash of the coming age of space; we mean to lead it.” That would require LOTS of scientific progress, technological innovation, national commitment, and most important, hard work. NASA’s scientists, engineers, mathematicians, technicians, and staff would be pushed to their limits. But the payoff would be immeasurable new knowledge, new solutions, new jobs, new discoveries, and much more. Just a month before JFK summoned the national will for space exploration, Julia Hernandez, a Mexican American farm worker in California, gave birth to her fourth child, José Moreno. He joined his hard-working family of migrant workers, and in his school years picked everything from grapes to cucumbers, moving in California with each harvest, his family splitting their time between Mexico and the US. That is -- until his second-grade teacher in Stockton, California came to visit his parents. She had learned the family was getting ready to move on, but she sensed promise in José. She stressed the importance of stability for the education of their children. Julia and Salvador Hernandez took her counsel to heart, settling in Stockton.  José said that on that day, his life changed forever. He continued to help his family but excelled in school. Inspired by the Apollo 17 moonwalks at age ten, he looked up at the stars at night and longed to be part of space exploration. He went on to earn a bachelor’s in electrical engineering, then a master’s degree in electrical and computer engineering. But his childhood dream of becoming an astronaut eluded him. José applied to NASA’s astronaut program not once, not twice, but twelve times. He was rejected eleven times. But this poster child for perseverance was undeterred. He kept studying, sharpening his skills, and increasing his chances. In May 2004, he was accepted into the astronaut training program! He trained hard, and by July 2008 was assigned to the crew of Space Shuttle Mission STS-128 to the International Space Station. As a mission specialist aboard, he realized his childhood dream of space exploration and, in the process, became the first Latino migrant worker to ever become an astronaut. José (who is now 62) has some advice for young people who have big dreams, but face great obstacles. “Don’t be so quick to give up on your dreams if you fail once or twice; sure, failure doesn’t feel good, sure, rejection doesn’t feel good, but if you prepare yourself, you come back stronger and eventually, you’ll get there.” José did.

And fortunately for all of us, Amazon wants to spread the word of his success. Their new original movie “A Million Miles Away” tells his story, and for the most part accurately (according to José). It’s a tale of incredible perseverance, hope, courage, and diligent pursuit of dreams. It’s an inspiration for kids and adults of all backgrounds. In October, as the “back to school blush” is off the rose, children in Core Virtues schools focus on the virtues of diligence, perseverance, patience, and self-control. They are being asked to stretch and push themselves “despite difficulty and hardship.” In other words: we choose to master reading in the first grade, long division in the fourth grade, essay-writing in the sixth grade, not because it is easy, but because it is hard. Go for it, kids! Mary Beth Klee José has told his own story for young adults in his memoir From Farmworker to Astronaut (Piñata Books, October 2019). |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |