|

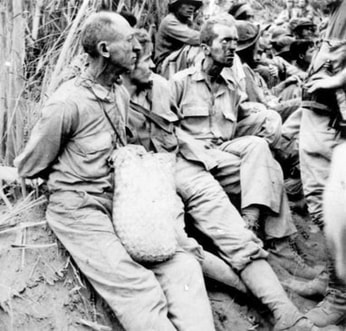

We ran a version of this article in May 2020. But its conclusions are even more timely as research on "hope" grows in the field of positive psychology. Hope, we are learning, is not an optimistic feeling, but an openness to seeing possibility in what lies ahead and -- even as we mourn loss -- an embrace of new opportunities.  So begins Emily Dickinson’s poem about one of the three great virtues, and it's a beautiful poem, but my reflections on Hope are grittier. Hope Johnson Miller was thirty-eight-years-old when she was captured by the Japanese and became a prisoner of war. An American school teacher married to a mining engineer, Hope and her husband had made their pre-war home in Manila, where they had a lovely home, servants, a driver, and shared the social life of American ex-pats overseas. As tensions mounted with Japan in late 1941, Hope’s husband answered General MacArthur’s call to enlist in the armed forces. Hope was alone in January 1942, when the Japanese invaded the Philippines, and imprisoned four thousand Allied civilians in Manila’s Santo Tomas Internment Camp (STIC). Three years of overcrowding, disease, cruelty, and starvation followed. Hope, who hailed from New Hampshire, had a gravelly voice and a granite-edged intellect. Known for her acid humor and the cigarette that was her constant companion, she was not the poster child for an Emily Dickinson illustration. No “thing with feathers” she. But over the next three years she taught those she befriended about the virtue for which she was named. Here are some lessons she taught. Hope endures: by late 1942 Hope learned that her husband George had been captured by the Japanese, endured the infamous Bataan Death March, and perished in the hell hole military camp of Cabanatuan. Stories about the cruelty of that march and that camp had filtered into Santo Tomas as early as August. When Hope learned her married life was over, she wept and inwardly raged, but she did not wallow in paralyzing grief. Instead…. Hope works: she labored, losing herself in the needs of the camp’s children. The camp’s industrious grown-ups had set up a makeshift school for the seven-hundred imprisoned kids. Hope now returned to overcrowded, makeshift classrooms and taught fifth graders. A devotee of American literature and poetry, she relished introducing her young charges to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (“The Song of Hiawatha”), Walt Whitman (“I Hear America Singing”), John Greenleaf Whittier ("The Barefoot Boy") and the newly popular Robert Frost (“The Road Not Taken”). She was a demanding teacher, who insisted on diagramming of sentences and memorization of verse, and STIC fifth graders both feared and admired Mrs. Miller. They admired her all the more when Allied bombers and Japanese Eagles tangled in the skies over their rooftop classrooms in 1944 spewing shrapnel and dropping bombs, and Hope insisted on being “last off the roof.”  Hope plans. Though she clung to the dream that American troops would soon liberate them, Hope did not put her trust in imminent release from danger. By late 1944, STIC prisoners were dying each day of starvation: she herself weighed less than 90 pounds. On September 22, 1944, the day after the first American planes overflew the camp and bombed Manila harbor (signaling to internees that help was on the way), Hope was on her knees outside her shanty, planting a little garden. When confronted by incredulous friends, who demanded to know what she was doing when liberation was only “days away,” she reminded them of the story of the Little Red Hen, and begrudgingly some decided to help her. Indeed, for the next four months that garden bore fruit (actually, spinach-like talinum, garlic, and mint) to tide them over. Hope draws on memory. Hope Miller’s memories were partly those of her Granite State girlhood at the foot of Mount Sunapee and of her husband, George. But hers was also the shared American memory: a sense of her nation’s story and her connection to it, a deep conviction that she was part of her country’s historic quest for freedom, liberty, and the wide open spaces that epitomized those qualities. For a Thanksgiving Day performance, after ten months of captivity, Hope had her fifth graders memorize and perform Stephen St. Vincent Benet’s, “The Ballad of William Sycamore.” In that poem, a Great Plains pioneer laments losing his two sons in battle -- one, at the Alamo and another at Little Big Horn, but “still could say, ‘So be it.’ But I could not live when they fenced the land, for it broke my heart to see it.’” On folding chairs, behind the iron bars of Santo Tomas, there was not a dry eye in the house. On Washington’s Birthday in 1944, Hope participated in a reading of Maxwell Anderson’s play, Valley Forge. Freedom, the play reminded these Americans in captivity, was often forged in time of trial. Endurance was part of the national drama. Hope shares. In mid-February, days after they were liberated, a young soldier sat next to Hope in the halls of Santo Tomas, staring at the emaciated men and women newly rescued and quietly taking in the cracked walls and squalid living conditions. While other GIs joked and chatted with internees, this “Still-Waters-Run-Deep” fellow put his hand on Hope’s forearm and said quietly, “Tell me. Did you ever despair?” In her written memoir, Hope writes, “My answer seemed very important to him.” And truth be told, if anyone had reason to despair it might have been Hope, who would return to the United States at age forty-one, widowed, childless, and penniless … to start all over. But instead, she couldn’t suppress a smile, took a drag from her cigarette and exhaled with satisfaction. “No. You see,” she turned toward the young man as if it were very important that he understand each gravelly word, “We knew you’d come back. We just knew it.” She held his eyes for a long moment and relished the childlike smile that suffused his face. Faith, hope, and love. In times of darkness, perhaps the greatest of these is hope. Psychologists tell us HOPE is not a feeling but a verb. It is the forward-looking, can-do reach for possibilities. True hope teaches us to endure, leads us to work, prompts us to lose ourselves in the needs of others, and draws strength from memory: our own treasured stories and those of others in our land, those who persevered in times of adversity. Hope ascends in an upward spiral when shared. Here's to Hope, my Sunapee friend and exemplar. Mary Beth Klee is the author of Leonore’s Suite, a novel about the experience of American civilians interned by the Japanese in Santo Tomas. Hope Miller's story is told therein and draws on Hope Miller Leone’s unpublished manuscript, Nor All Your Tears.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |